Most of Katsushika Hokusai’s books were offered for sale in a highly competitive market. The driving force behind production was the publisher. He commissioned the artist and the author (or editor) if there was to be text, and he hired a calligrapher to write out any texts and a copyist to assist in the preparation of the block-ready drawings. He then engaged the block cutter, the printer, and the collator/binder. Finally, he arranged for the distribution and sale of the finished book through affiliated firms of booksellers and commercial lending libraries.

Book Binding

Almost all of Hokusai’s books were issued in the side-stitched binding favored by commercial publishers throughout the Edo period (1615–1868). The component parts of these side-stitched volumes are all made of paper: the book block, the inner binding, and the covers. Consequently, they do not expand and contract differentially in response to changes in atmospheric conditions, and a source of stress to the fabric of the book is eliminated. The paper employed is long fibered and acid free, assuring a robust, flexible product.

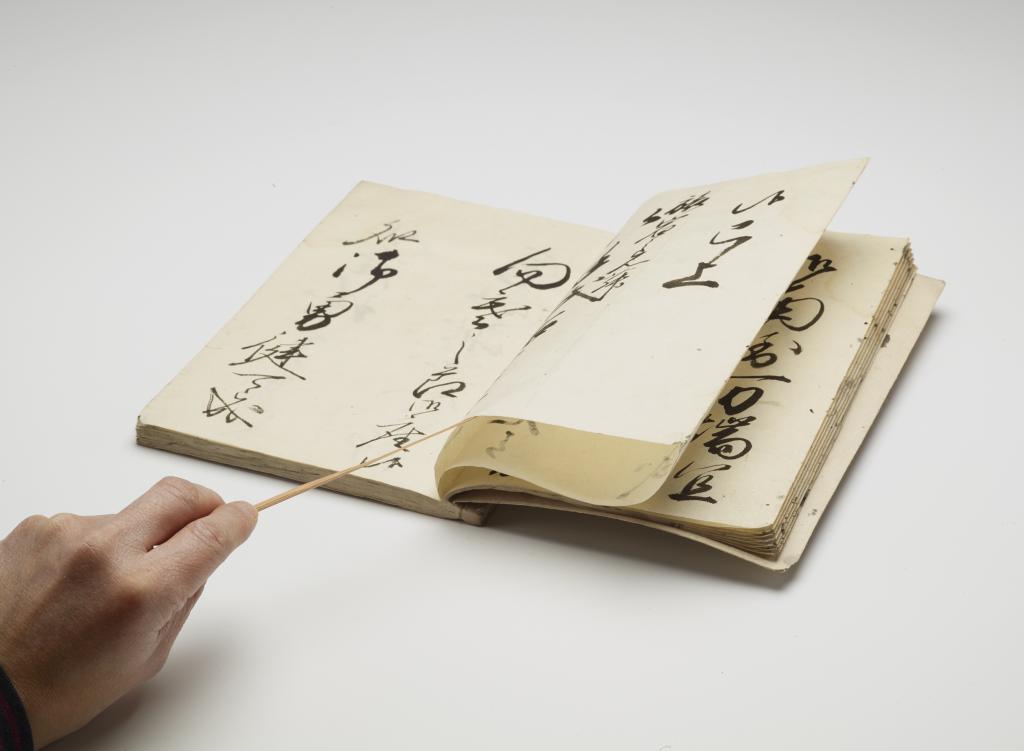

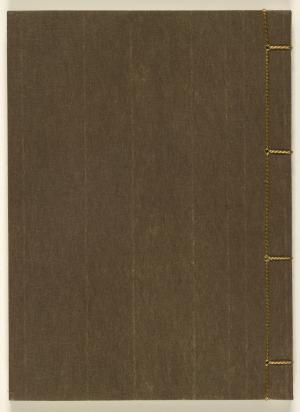

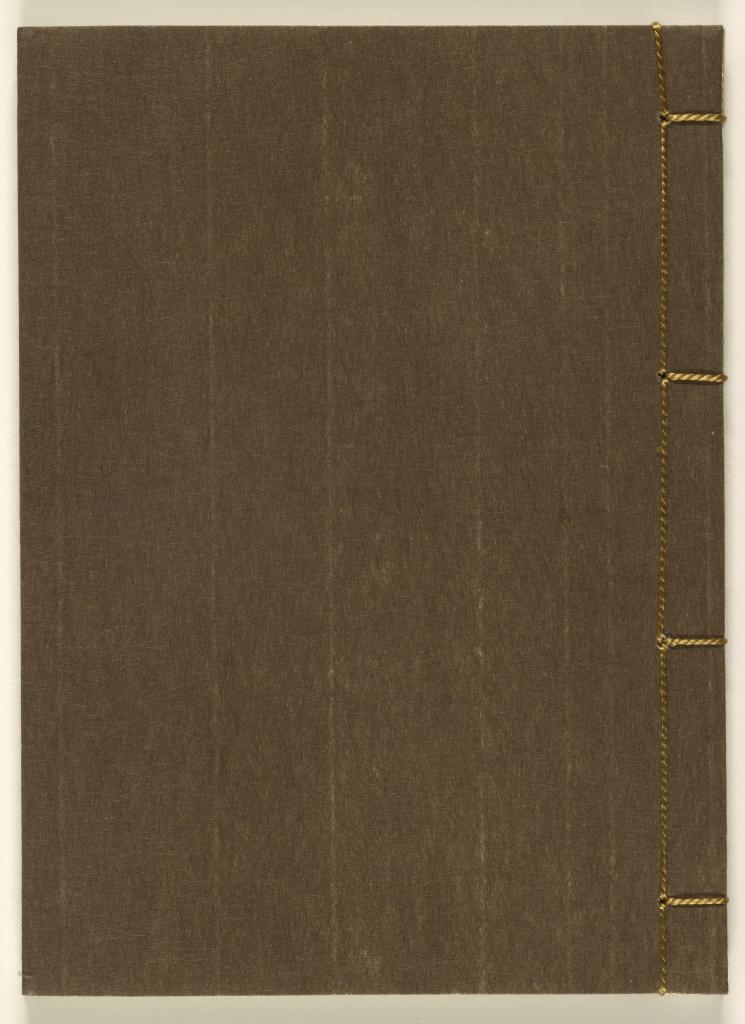

In addition to the side-stitched binding, a second distinguishing feature of these books is the structure of their pages. Each page is formed from a single sheet of paper printed on one side only and then folded with the printed side out Fig. 1. The folded sheets are collated, stacked, and bound together at their open ends with two short cords of twisted paper. Each cord is passed through a pair of holes punched through the stacked sheets and then tightly tied. These cords form the inner binding and hold the stacked sheets that constitute the book block firmly together. The folded ends of the sheets form the fore-edge of the book block. The top and bottom corners of the spine are often enclosed within silk edging Fig. 2. Finally, the front and back covers are glued to the blank outer pages of the book block and are securely attached to it using a single length of hemp cord stitched through four holes punched through the covers and book block Fig. 3. (The latter are distinct from the two pairs of holes employed for the inner binding.) This is the “stitching” from which the English name of this binding is derived. In Japanese this binding is called fukurotoji. Toji means “binding”; fukuro encompasses “bag,” “pouch,” and “layered” and alludes to the folded sheets that make up the pages of these books. Hereafter, fukurotoji will be used when referring to this binding format. The finished fukurotoji book is a sturdy artifact that stands up well to use.

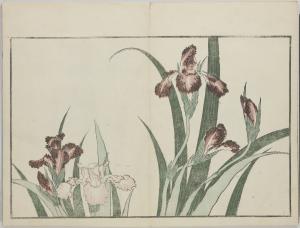

A very small number of Hokusai’s books were published in “album format”(gajōsō, also known as gajōjitate). In this format, each opening is formed by a single sheet of thick, high-quality paper printed on one side only, folded with the printed side in, and glued at the outer edges to the preceding and following sheets. The outermost half-sheets are attached to stiff covers. The covers are joined by a strip of fabric that protects but is not attached to the folded ends of the sheets that make up the spine of the book. This format is less robust than fukurotoji but offers an unbroken image field (see below). Some of the most luxuriously produced books of the Edo period are in this format. Outstanding among the very few books by Hokusai produced in this format is Hokusai shashin gafu Fig. 4.

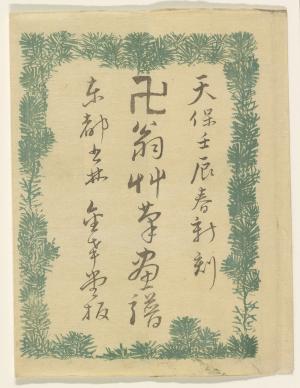

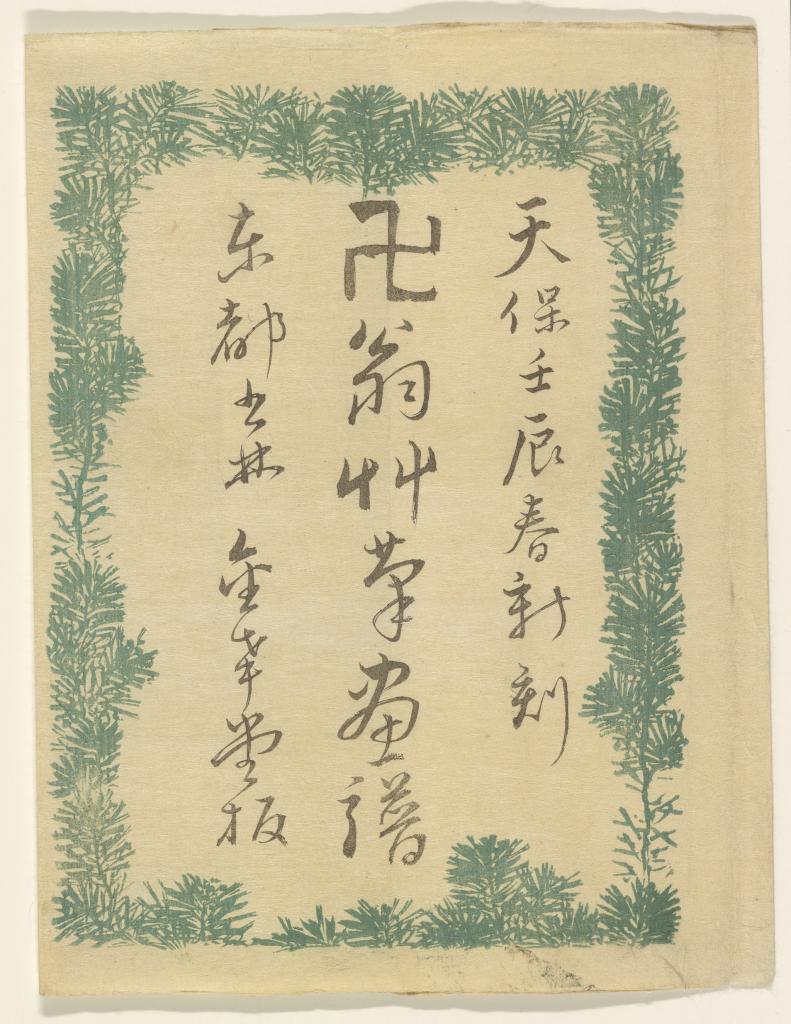

Protective Wrapper

Books were offered for sale in protective paper wrappers Fig. 5. These wrappers consist of a single sheet of paper, the height of the book, that was wrapped tightly around the volume(s) and glued onto itself at the back. The top and bottom of the volume(s) remain exposed. These wrappers usually carry little more than the book title plainly printed in black; on rare occasions they were color-printed with complex decorations. Hokusai created some highly sophisticated designs for the wrappers of books such as his (Ehon kyōka) Yama mata yama and Fugaku hyakkei.

Wrappers were meant to protect a new book before sale. They are not like dust jackets that can remain on the book while it is being read. It is very difficult to slide a book back into its wrapper once the book has been removed. Thus very few wrappers survive. Sometimes a decorated wrapper was trimmed down and pasted onto the front cover (or the inside front cover) of the book for which it was meant.

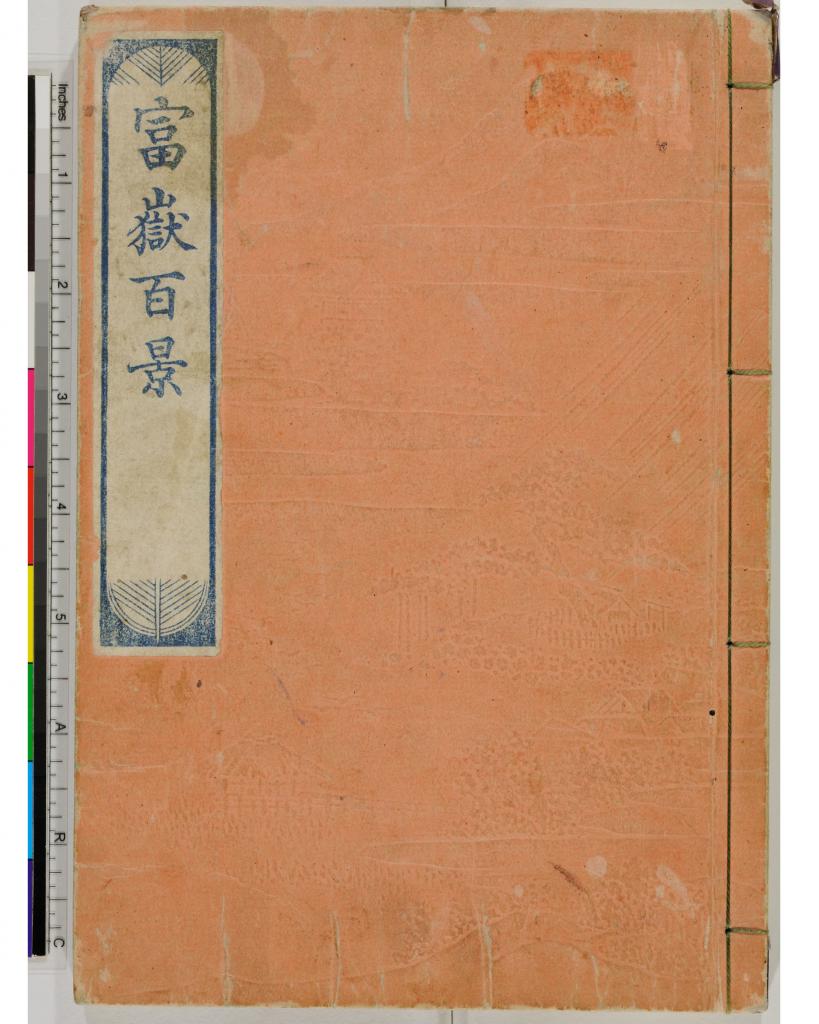

Covers and Title Slip

In fukurotoji books a slim, rectangular printed paper title slip is pasted onto the front cover of each volume Fig. 6. It is usually placed in the top left corner; less often it is centered on the cover. It supplies, as its name implies, the title of the book. The title may be preceded by two columns of half-size characters that indicate something about the book. For example, the characters may read “with pictures added” or “printed from newly cut blocks.” These header texts are not treated as part of the title when identifying, listing, or indexing a book. The title proper on the title slip is usually followed by the character zen or kan if the book is complete in one volume. In the case of books published in more than one volume, the title is followed by a numerator indicating the number of the volume. Often non-numeric numerators are used, such as “top, middle, bottom,” “Heaven, Earth, Man,” or “East, West, South, North.” Minimal decoration appears on the title slips, usually no more than one or two thin lines framing the text.

The covers themselves are complex objects. They consist of a core of pulped scrap paper enclosed within highly finished paper that is dyed and often decorated Fig. 7. Printing, burnishing, stenciling, impressing with patterns, molding with relief decorations, and painting by hand are all techniques used to decorate covers. The covers of a title offered for sale by a publisher over an extended period could vary considerably in terms of color and decoration. However, some publishers used a standard cover type over many years, making their books immediately identifiable and helping to establish their brand. Cover decoration is usually understated. Elaborately decorated, multicolor covers are encountered only in nineteenth-century erotic books and certain genres of popular literature.

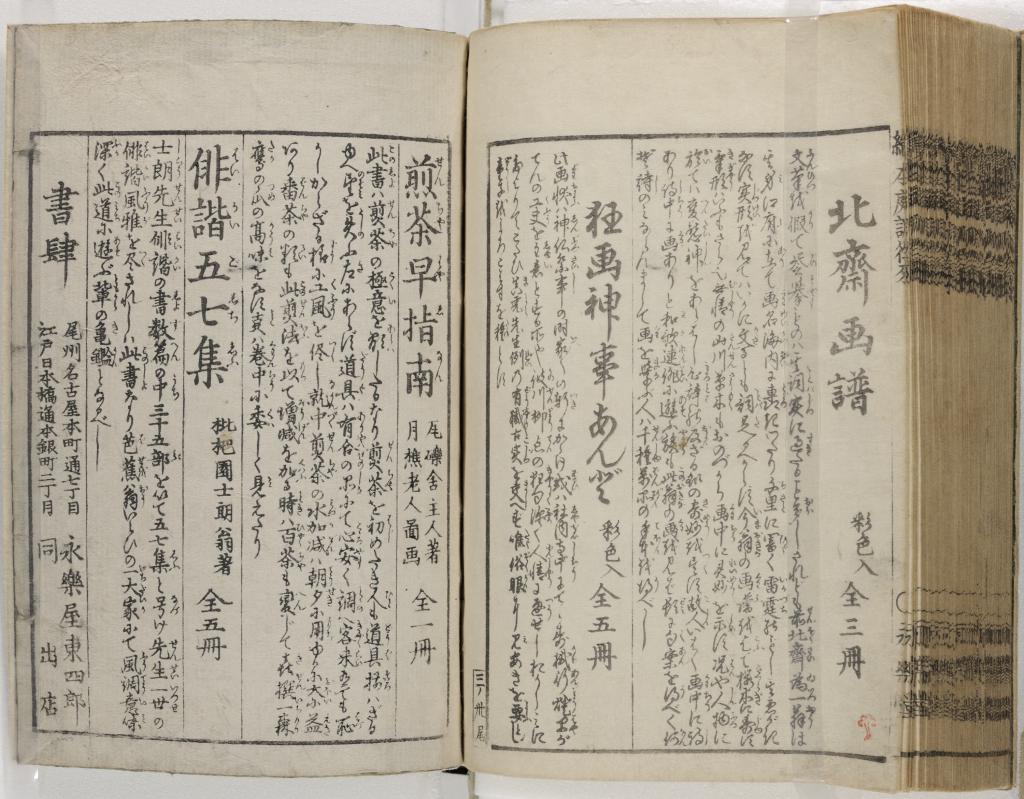

Lack of a Title Page

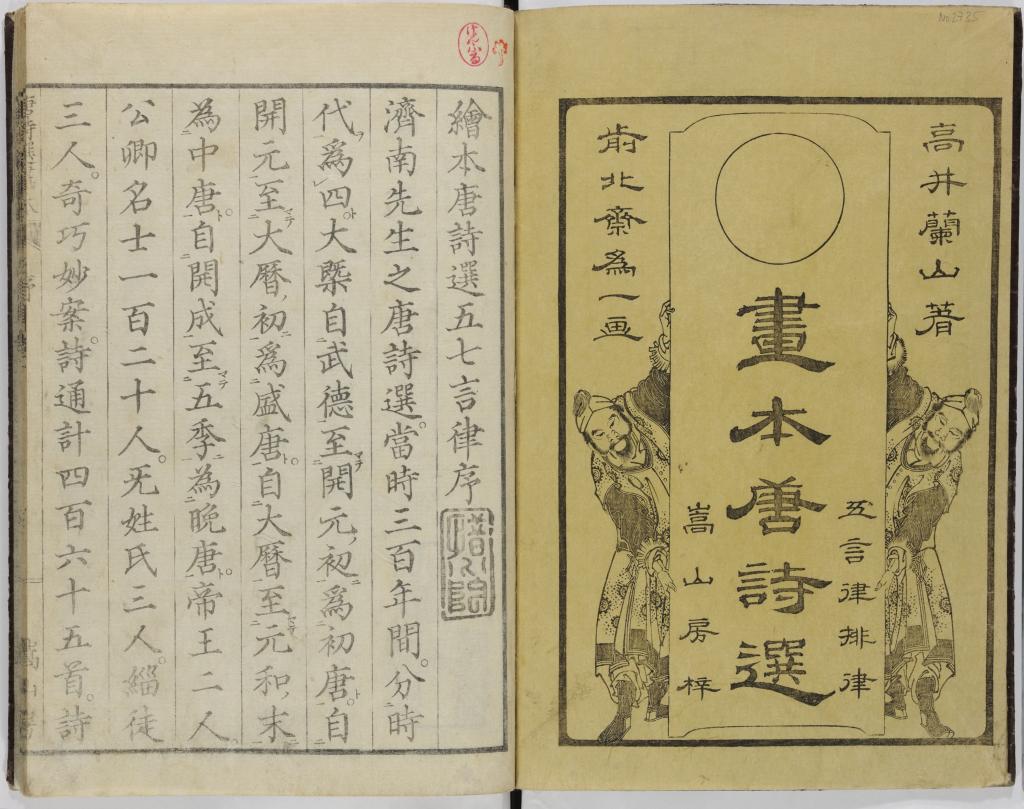

There is no standardized title page in Japanese books of the early modern era. This does not mean they were untitled. Quite the contrary: some suffer from too many titles. The title on the title slip has already been noted. In addition, a book may have a printed sheet bearing the title appearing on the title slip or a variant thereof pasted on its inside front cover Fig. 8. (In books of more than one volume this sheet appears only on the inside front cover of the first volume.) Further possibly variant titles may be found at the head of the preface, at the head of the table of contents (if there is one), at the beginning of the main text, in the pillar (see below), and/or at the end of the main text. All of these are optional; the only place where a title will always be found is on the title slip. Bibliographically, this practice invests the title slip title with great importance. By common consent, it provides the “uniform title” by which a book is identified, catalogued, listed, and written about today.

Book Layout

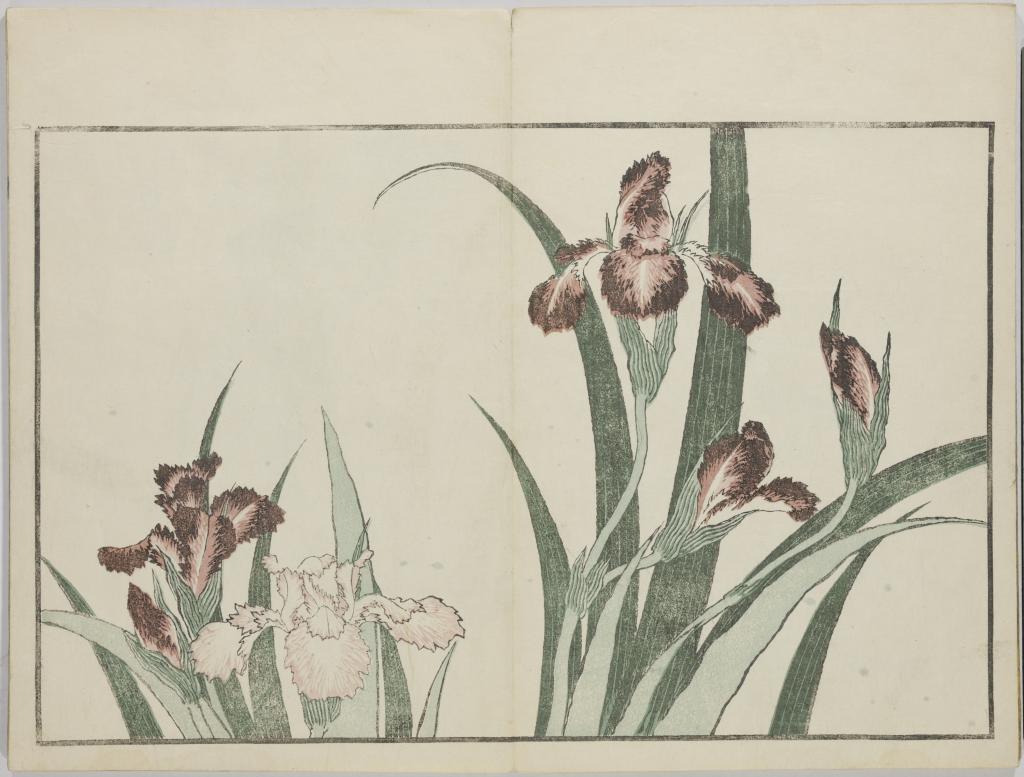

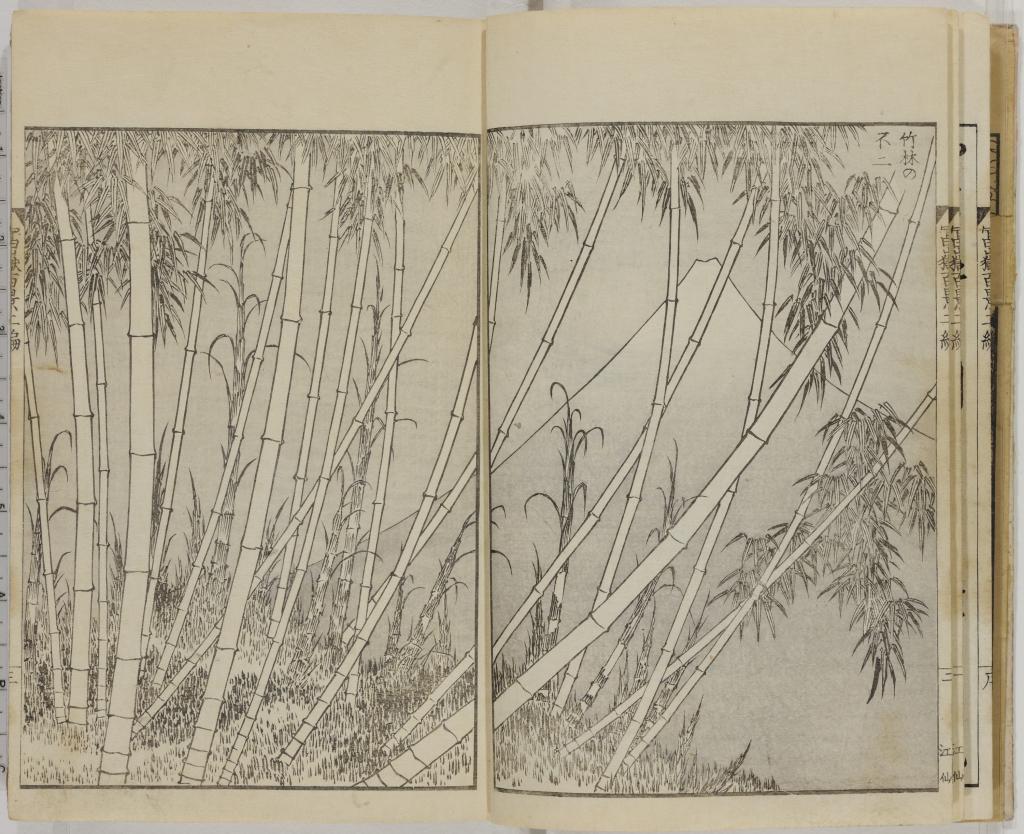

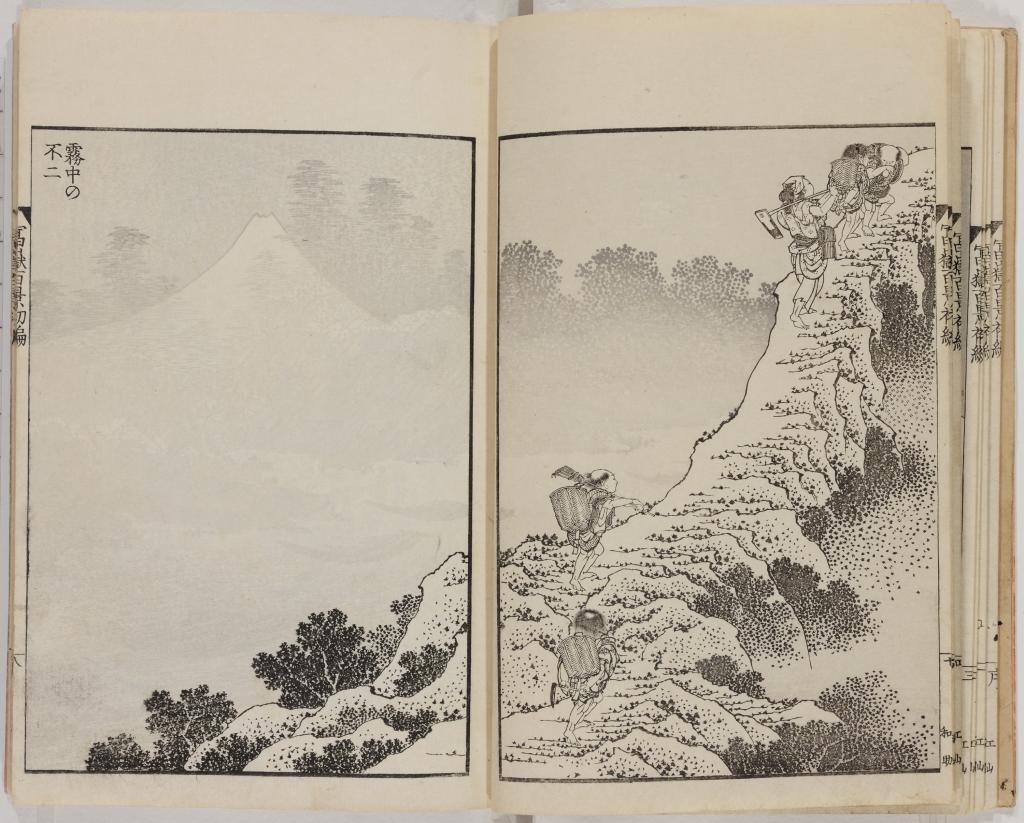

The printed area (the text and image field) of each page in a fukurotoji book is enclosed within a printed, single-line frame Fig. 9. (Only a very small number of books, usually those written in cursive Japanese syllabic script, omit the field frame.) There are clearly demarcated margins on all four sides of the printed area on each page. Nonetheless, the standard design unit is the double-page spread, not the single page. Text and images flow from right to left across the double-page spread, but neither image nor text bleeds into the central well or gutter. There is always a central divide. Artists of all schools proved adept at creating designs that crossed that divide. Once the viewer has become accustomed to this convention, any sense of disjunction between the two halves of the image disappears. Very occasionally, the artist deliberately allows an element of a design—perhaps a mountain peak or a spear tip—to extend beyond the frame of the image field into the top margin.

Due to the way in which fukutotoji books are made, each half of the double-page spread is printed in a separate operation from a separate block. This system does not cause particular problems with books printed in black ink only, but multicolor woodblock-printed illustrations that span the double-page spread require particular care on the part of the printer to guarantee the colors on the facing pages match. Because each color is printed from a separate block, a thicker grade of paper that can withstand repeated printings is used for multicolor books. The thicker grade of paper, the costly color pigments, and the multiple printing of each sheet substantially increased the cost of production. Very few of Hokusai’s books contain multicolor images, and those that do are either privately commissioned poetry anthologies, such as (Ehon kyōka) Yama mata yama Fig. 10, or erotica, such as Kinoe no komatsu.

To enliven and vary picture books, publishers had recourse to a cheaper alternative. It involved employing two additional sets of blocks to add pale pink and gray tints to the line-only images printed by the key block. The dilute pigments employed in these books did not require the thicker and more expensive paper needed for printing in multiple, saturated colors. Use of this limited palette had its origins in the closing decades of the eighteenth century. It was then taken up for the Hokusai manga and other books of images by Hokusai and his contemporaries. A more subtle variant employed the extra blocks to print in shades of gray. The finest example of this monochrome combination is Hokusai’s Fugaku hyakkei.

Publisher’s Data

Reform of the printing industry in 1722 mandated the presence of a colophon at the end of every commercially issued book Fig. 11. (In books published in more than one volume [satsu], such as Hokusai’s [Ehon kyōka] Yama mata yama, the colophon appears at the end of the final volume. In serial titles such as Hokusai manga, which were published in parts [hen] at irregular intervals, there is a colophon at the end of each volume.) The colophon provides the name and address of the publisher(s) and distributor(s) of the book. It also records the “year of production” (hannen), that is, the year in which the blocks from which the book is printed were cut. The actual year of printing is not given. The colophon also lists, as appropriate, the names of some or all of the following: author, editor, artist, and calligrapher. In cases where the cutting of the blocks required particular skill and attention, the name of the block cutter is also recorded. Even more rarely, the name of the printer is given. (The printer’s name is excised from the block for later printings of the book if the work is assigned to other, less-skilled hands.) The colophon does not include the book title.

If a set of printing blocks was sold to another publisher, the colophon was modified. The original publisher’s name was cut out of the block; a wood plug was inserted into the block and cut with the name of the new publisher. Sometimes a second date was added to the colophon to indicate the year in which the printing blocks changed hands.

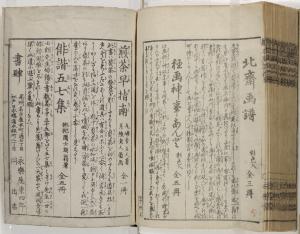

The first printings of all of Hokusai’s commercially produced books carry colophons; the colophons were omitted when the books were reprinted by the Nagoya firm of Eirakuya Tōshirō. The latter removed them in order to hide the fact that many of the books on this list were being published from blocks cut forty years previously. Perhaps because the firm was based in Nagoya, it was easier to ignore the requirement that all commercially issued books carry a colophon. Instead of a colophon, sheets advertising other books available from the firm were pasted on the insides of the front and back covers of these books. The advertisement on the inside of the front cover usually carried a header naming the firm. The advertisement on the back inside cover sometimes provided the firm’s full name and address in a narrow side panel. Eirakuya Tōshirō appears to have reached a modus vivendi with the authorities, as these colophon-less editions circulated widely throughout Japan.

The Pillar

A unique feature of fukurotoji books is the pillar, the space between the two blocks of text and/or images printed on the sheets that are folded to form each page of the book. Text is often printed in the pillar. When the sheet is folded, the text straddles the central fold: half of it was visible on one side of the page, half on the other Fig. 12. The pillar usually carries some or all of the following information: the book title, often in abbreviated form; the volume number; the number of the sheet; and the publisher’s name. Note that the sheets making up the book are numbered but the pages formed by them are not.

Back Matter

Back matter (okuzuke) consists of sheets printed separately from the sheets making up the book block but bound with them. They range from six or more folded printed sheets to just a half-sheet pasted on the inside back cover Fig. 13 Fig. 14. Back matter usually consists of lists of books produced by the publisher, which can run to many pages. (In works of popular literature intended for a mass audience, advertisements for other products such as cosmetics and medicines may be included in the back matter.) The same back matter is often found bound into a number of different books. The blocks from which back matter was printed were regularly modified to keep their content up to date.

Types of Printing and Coloring

A number of types of printing and coloring are encountered in Edo period books. The most common are:

- Printing from a relief block in black ink to produce black-on-white texts and images (sumizuri) Fig. 15

- Printing from two or more relief blocks in various shades of black ink (sumizuri with usuzumi) Fig. 16

- Printing from multiple relief blocks in many saturated colors (tashokuzuri) Fig. 17

- Printing from three relief blocks in black and a limited range of light tints, usually pink and gray (tanshokuzuri) Fig. 18

- Stenciling, applying colors by brush to sheets printed with line-only illustrations, using a separately cut stencil for each color (kappazuri)

- Printing areas in one color of graduated intensity by the differential application of a pigment to a relief block (bokashi) Fig. 19

- Applying colors by brush to sheets printed with line illustrations (hissai)

- Impressing patterns into a sheet of paper from an uninked relief block (karazuri).

Publishing

Japanese publishers did not store large numbers of printed books; after the initial print run, which might be no more than a few hundred copies, they stored the printing blocks and used them again as demand required often over many years. In some respects, they practiced a form of printing on demand. The blocks cut for very popular books like Hokusai manga and Fugaku hyakkei were used for decades. On each occasion that the blocks were used, a relatively small number of copies of the book were printed.

The grade and size of the paper used, the presence or absence of color, the quality of the pigments used when color is present, the condition of the blocks, the choice of covers, and the care taken by the printer could and did vary from printing to printing. It is best not to use the English word “editions” when discussing Edo period books; “printing” is preferable unless it is clear that a new set of blocks is being used.

The material required to produce a book comprised paper of a standard size and quality, which consumed most of the production budget; prepared woodblocks of standard size; pigment(s); twisted paper cord for the inner binding; covers prepared by specialist manufacturers; and hemp thread to secure the covers to the book block.

Folded sheet opened to show sheet folded with text or image side outside

Fukurotoji binding showing silk reinforcement at corner (kadogire)

Complete fukurotoji binding showing typical stitching pattern for outer binding

Album binding

Hokusai shashin gafu 北斎写真画譜

Artist: Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849)

Edo period, 1814 (Bunka 11), spring

1 volume; fukurotoji binding; woodblock printed; ink and color on paper; paper covers

25.7 x 17 x 0.8 cm

Freer Gallery of Art, FSC‑GR‑780.237

Fukurowrapper for

Manjiōsōhitsu gafu 卍翁艸筆画譜

Artist: Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849)

Edo period, 1843 (Tenpō 14); preface dated 1832 (Tenpō 3)

Fukuro (wrapper); fukurotoji binding; woodblock printed; ink on paper; paper covers

22.3 x 15.8 x 1.1 cm

Freer Gallery of Art, FSC‑GR‑780.251.2

Fugaku hyakkei 富嶽百景

Artist: Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849)

Edo period, 1834 (Tenpō 5)

Volume 1 of 3; woodblock printed; ink on paper; paper covers

22.9 x 15.8 x 1 cm

Freer Gallery of Art, FSC‑GR‑780.246.1

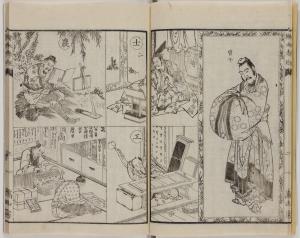

Hokusai gashiki 北斎画式

Artist: Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849)

Edo period, 1819 (Bunsei 1), 9th month

1 volume; fukurotoji binding; woodblock printed; ink on paper; paper covers

26.6 x 18.1 x 1.1 cm

Freer Gallery of Art, FSC‑GR‑780.223

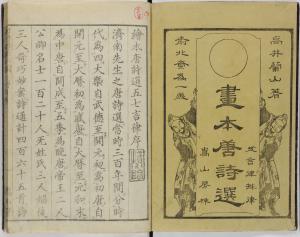

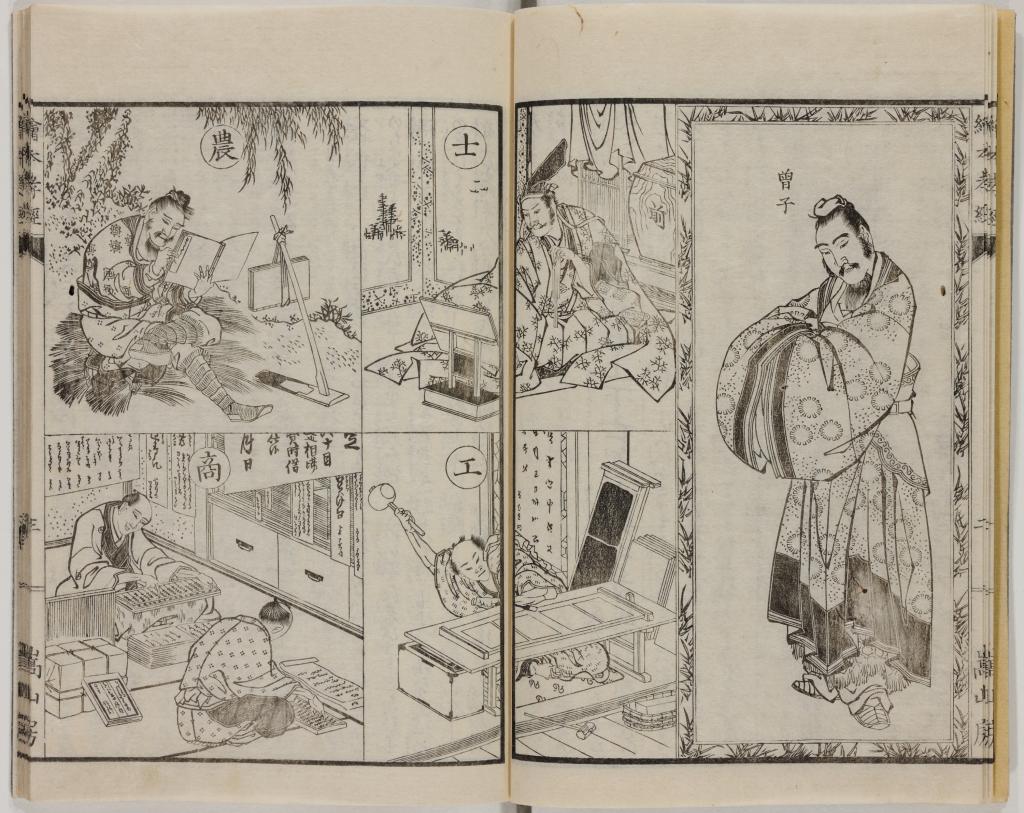

Tōshisen ehon gogon ritsu 唐詩選画本 五言律

Artist: Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849)

Edo period, 1833 (Tenpō 4), 1st month

Volume 1 of 5; fukurotoji binding; woodblock printed; ink on paper; paper covers

22.8 x 15.7 x 0.4 cm

Freer Gallery of Art, FSC‑GR‑780.218.1

Fugaku hyakkei 富嶽百景

Artist: Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849)

Edo period, 1835 (Tenpō 6)

Volume 2 of 3; woodblock printed; ink on paper; paper covers

22.9 x 15.8 x 1 cm

Freer Gallery of Art, FSC‑GR‑780.246.2

(Ehon kyōka)Yama mata yama 画本狂歌 山満多山

Artist: Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849)

Edo period, 1804 (Kyōwa 4), spring

Volume 1 of 3; fukurotoji binding; woodblock printed; ink and color on paper; paper covers

26.7 x 17.5 x 0.6 cm

Freer Gallery of Art, FSC‑GR‑780.236.1

Tōto shōkei ichiran 東都勝景一覧

Artist: Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849)

Edo period, 1800 (Kansei 12), 1st month

2 volumes; fukurotoji binding; woodblock printed; ink and color on paper; paper covers

25.8 x 17.5 x 0.5 cm

Freer Gallery of Art, FSC‑GR‑780.217.2

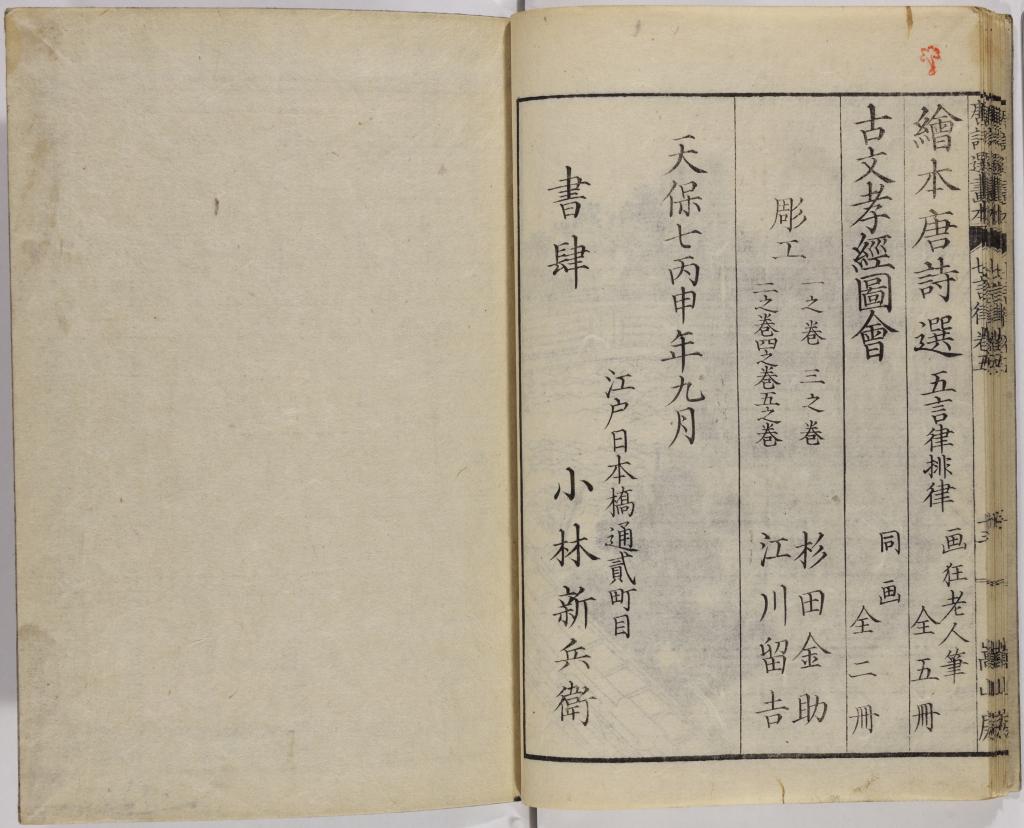

Ehon kōkyō 絵本孝経

Artist: Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849)

Edo period, 1864 (Genji 1), winter

Volume 1 of 2; fukurotoji binding; woodblock printed; ink on paper; paper covers

22.8 x 15.8 x 0.6 cm

Freer Gallery of Art FSC‑GR‑780.221.1

Tōshisen ehon shichigonritsu 唐詩選絵本七言律

Artist: Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849)

Edo period, 1836 (Tenpō 7), 9th month

Volume 5 of 5: fukurotoji binding; woodblock printed; ink on paper; paper covers

22.8 x 15.7 x 0.4 cm

Freer Gallery of Art, FSC‑GR‑780.226.5

Ehon teikin ōrai 絵本庭訓往来

Artist: Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849)

Edo period, 1828 (Bunsei 11), 9th month

1 volume; woodblock printed; ink on paper; paper covers

22.8 x 15.9 x 3.3 cm

Freer Gallery of Art, FSC‑GR‑780.225

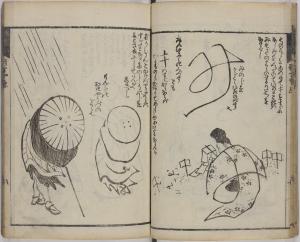

(Ryakuga haya oshie sanpen) Gadōhitori geiko(略画早指南三篇)画道独稽古

Artist: Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849)

Edo period, 1812 (Bunka 9)

Volume 2 of 3; woodblock printed; ink on paper; paper covers

18.6 x 13.1 x 0.7 cm

Freer Gallery of Art, FSC‑GR‑780.253.2

Fugaku hyakkei 富嶽百景

Artist: Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849)

Edo period, 1834 (Tenpō 5)

Volume 1 of 3; woodblock printed; ink on paper; paper covers

22.9 x 15.8 x 1 cm

Freer Gallery of Art, FSC‑GR‑780.246.1

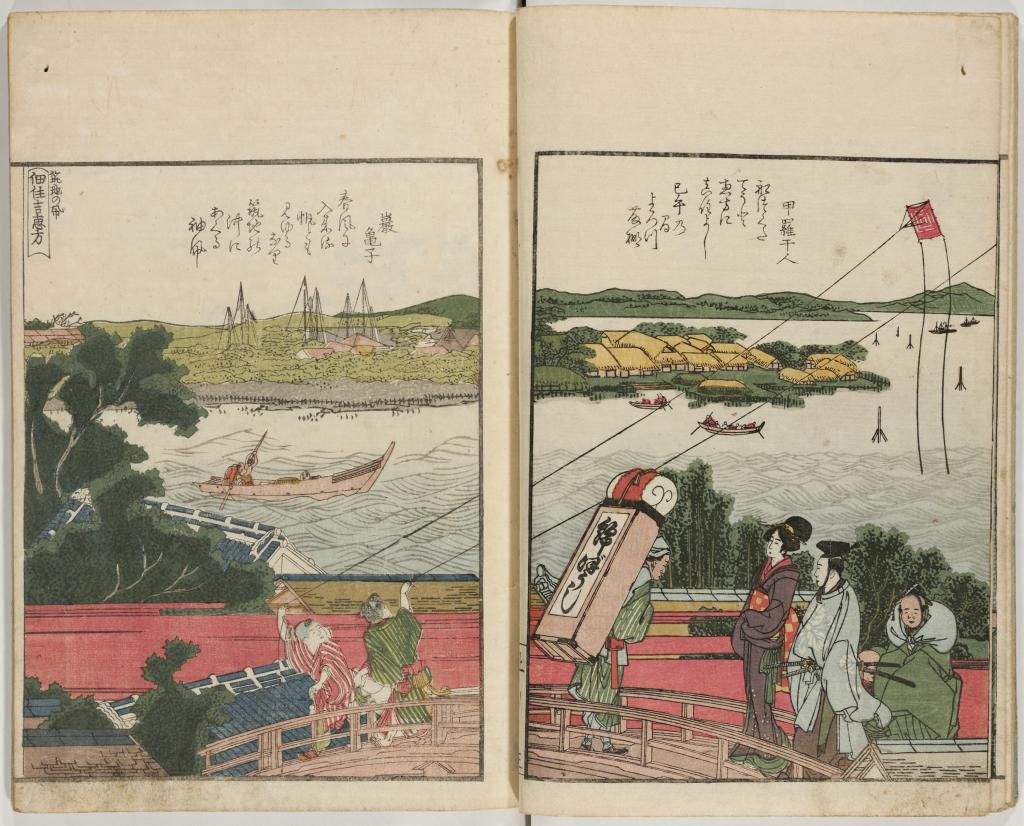

Ehon Sumidagawa ryōgan ichiran 絵本隅田川 両岸一覧

Artist: Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849)

Edo period, ca. 1805

Volume 1 of 3: woodblock printed; ink and color on paper; paper covers

26.5 x 18.3 x 0.4 cm

Freer Gallery of Art, FSC‑GR‑780.230.1

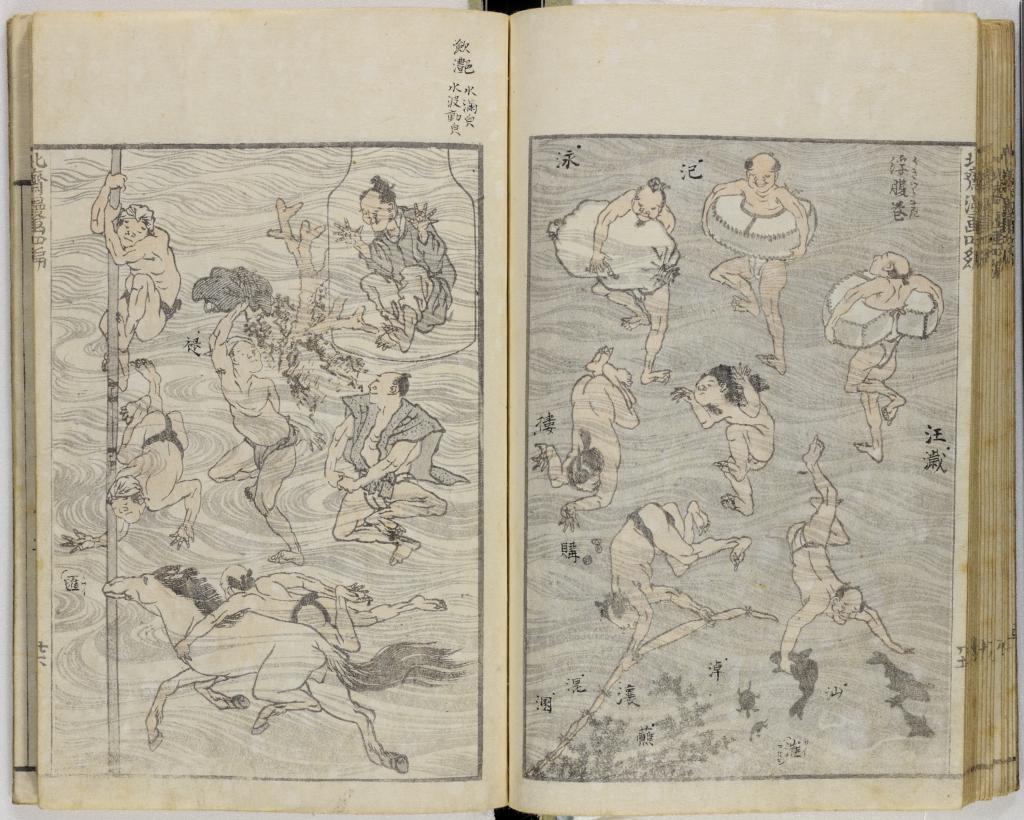

(Denshin kaishu) Hokusai manga (伝神開手)北斎漫画

Artist: Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849)

Edo period, 1814 (Bunka 11)–1878 (Meiji 11)

Volume 2 of 15: woodblock printed; ink and color on paper; paper covers

22.9 x 15.9 x 1 cm

Freer Gallery of Art, FSC‑GR‑780.233.2

Ehon Sumidagawa ryōgan ichiran 絵本隅田川 両岸一覧

Artist: Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849)

Edo period, ca. 1805

Volume 1 of 3: woodblock printed; ink and color on paper; paper covers

26.5 x 18.3 x 0.4 cm

Freer Gallery of Art, FSC‑GR‑780.230.1