Book publishing emerged as a commercial enterprise in Kyoto early in Japan’s Edo period (1615–1868). Here a remarkable expansion in the publication and dissemination of printed books coincided with a cultural renascence in scholarship, literature, arts, crafts, and architecture. Kyoto, the imperial capital since 794, had long flourished as a cultural center under the patronage of the imperial court, noble and warrior families, the Ashikaga shoguns (1336–1573), and Buddhist monasteries. Among the city’s cultural resources were repositories of manuscripts of religious, historical, legal, and literary texts in both Japanese and Chinese. It was also home to professional artists, calligraphers, and craft specialists with unrivaled expertise and skills, developed and refined for generations. A century of destructive warfare among powerful warlords abated following the decisive victory of Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543–1616) at the battle of Sekigahara in 1600. Although the Tokugawa shoguns established a new administrative center in Edo (modern Tokyo), where a distinct urban culture emerged, Kyoto remained a center of learning and cultural traditions. Here, in the relatively stable conditions at the beginning of the seventeenth century, the arts again flourished, revitalizing technical and design traditions with innovations that drew from Kyoto’s historical achievements and recast them in new and vibrant styles and media.

Technology and Publishers

The technology of printing on paper from carved woodblocks had been known in Japan since the eighth century, but hand-copying with brush and ink remained the dominant method for reproducing texts and images in handscroll and book formats until about 1600, when Kyoto artists and publishers began to develop methods of printing aesthetically attractive books. By 1650, merchants in Kyoto had recognized the commercial potential of book publishing, and new enterprises developed efficient methods for producing and marketing books. In time, commercially printed books became the primary carriers of knowledge, culture, historical and contemporary literature, amusements, and practical information.

Until the beginning of the seventeenth century, woodblock printing for texts and occasionally for talismanic images had been organized within Buddhist temples and monasteries, where the written language for religious and historical texts was Chinese. The technology of printing from type, however, was also known in Japan through the metal type brought back from the Korean campaigns of the hegemon Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536–1598). 1 The Jesuit Mission Press also published movable type books from a press imported from Europe. During the first half of the seventeenth century, movable wood type was created by Kyoto calligraphers and craft specialists to print books with Japanese texts in cursive hiragana phonetic script and Chinese characters.

Early books published at Saga, west of Kyoto, under the patronage of the merchant Suminokura Sōan (1571–1632) reflected the aesthetic sensibilities of his artistic collaborator, Hon’ami Kōetsu (1558–1637), the leading calligrapher of his time, and drew on the skills of papermakers, decorators, block cutters, printers, and type carvers, who created wood type fonts that reproduced the graceful forms of characters written with a brush. fig. 1 The Sagabon publications, relatively small editions designed for an educated readership with refined taste, revealed that the aesthetic qualities of superior calligraphy and painting could be reproduced by printing. 2

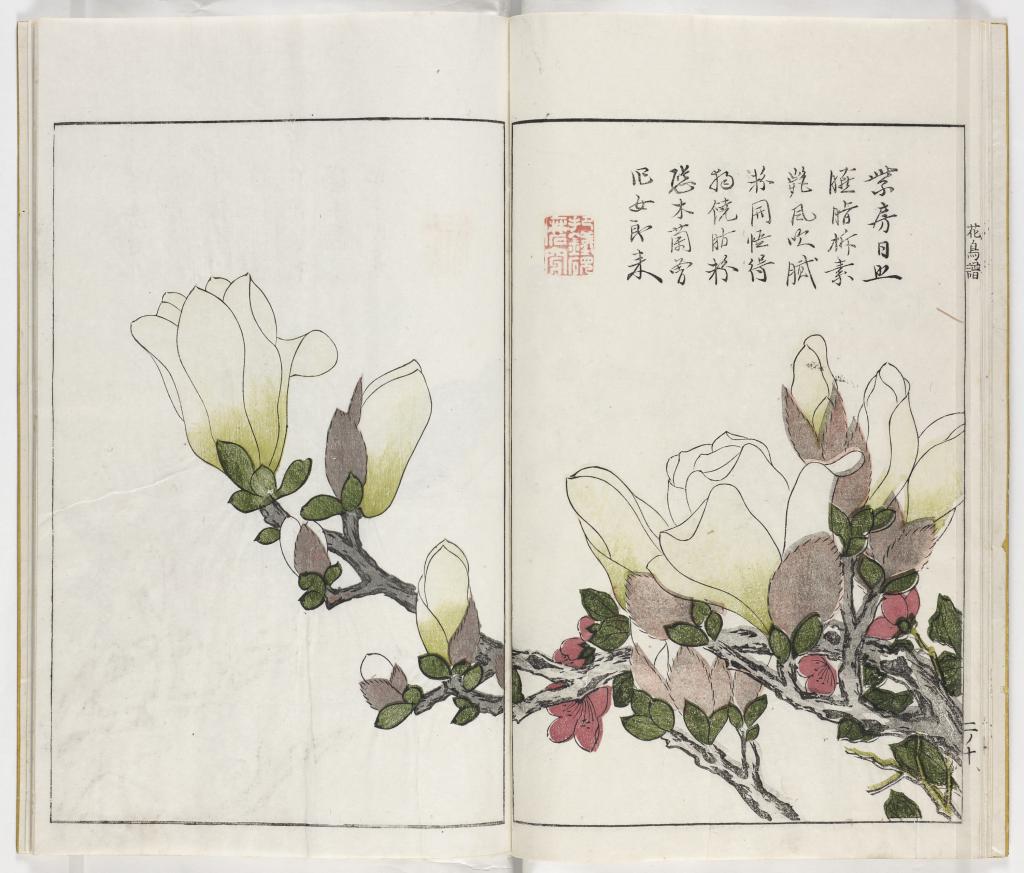

Among the Sagabon volumes were illustrated books, which constitute a relatively small subset among the vast corpus of Japanese printed books but survive disproportionately in rare book and museum collections today, especially outside Japan. Nonetheless, they must have been profitable for publishers seeking to reach new audiences beyond the culturally sophisticated and fully literate elite. fig. 2 In time, as commercial publishers increased their production and markets, illustration shifted from serving in a close, often subordinate, relationship with text to being independent of text, even the primary or sole content. Illustrated books with no text except for a preface became a highly successful genre that evolved and adapted to changing styles and purposes from the eighteenth century fig. 3 to the twentieth century, when print artists and photographers began to design and produce books to showcase their work fig. 4.

The introduction of images into printed books increased their interest and appeal for readers who ranged from bilingual scholars who read Chinese and Japanese fluently to a wider public who might read only phonetic scripts. Illustrated books with little or no text offered a visual experience that had no counterpart in the traditional arts fig. 5. For these works, publishers sought out accomplished and often renowned artists who drew on a long historical tradition of illustration that had developed for narrative fiction, poetry, and biographical and historical works in which text and image—all created with brush, ink, and color—were mounted in continuous handscroll, album, or stitched book formats.

During the second half of the seventeenth century, as merchants in Kyoto organized publication into a secular, commercial enterprise, publishers returned to the older technology of woodblock printing. The historian Peter Kornicki suggests that publishers may have recognized the inefficiency of setting type for a book and then having to reset it if a title proved popular and a reprint was necessary. In contrast, for a book printed from woodblocks, the blocks could be stacked, stored, and quickly reused for reprints. Blocks were also more durable than moveable wood type, allowing print runs of thousands of copies before wear required significant repair or replacement. Moreover, printed pages from the books themselves could be used to cut duplicate blocks that accurately replicated an edition in high demand. Equally important, woodblocks offered greater flexibility of page design, as text and image could be combined in any configuration on the page. Text, image, or text and image could be cut at the same time and printed from a single block, rather than on separate pages fig. 6.3

As sales of books increased, publishers promoted their books on the New Year, 4 when the simultaneous release of new titles created excitement among readers and buyers for bookstores. The consequent surge in sales was much like the effect of publishers’ book fairs today. Publishers inserted announcements of upcoming titles in books ready for sale—the simple fukurotoji stitched binding made insertion easy—and they occasionally added front matter or back matter listing other titles by the same artist or publisher fig. 7. Specialization, trademarks, and other self-branding by publishers also guided buyers to titles or artists of interest. Retaining the hankabu, or right to publish, was important to publishers, who faced competition from pirated editions, often made by disassembling a volume and using the sheets to carve new woodblocks for printing. The formation of publishers’ guilds created an internal system for resolving conflict, protecting the rights of members, and reviewing books prior to publication for problems that might bring sanctions from the shogunate. 5

Distribution

Book distribution benefited from improvements initiated by the shogunate in communications and transport. Bookshops that sold new publications were at first concentrated in Kyoto, but soon Kyoto publishers were distributing to shops in nearby Osaka and distant Edo, the rapidly growing governmental center of the Tokugawa shoguns. By the 1660s, there were bookshops in provincial cities. Itinerant booksellers also distributed books. Commercial lending libraries (kashihonya) further increased distribution by purchasing books and lending them to readers for a period of time at a fee that would be far less than the cost of owning the book. These libraries were the primary source for access to large, multivolume works, which were prohibitively expensive for most individual readers.6 Such volumes were usually published in smaller quantities, since the publisher bore the risk and expenses of commissioning the calligraphy and illustrations, blocks, paper, and labor for printing, binding, and distribution, whether or not the books were sold (fig. 8). Books on loan were sometimes hand-copied for study, further lending, or exchange, thus amplifying the impact of commercial lending libraries (or personal lending) in making books available to an even greater number of readers. By the early nineteenth century, thousands, even tens of thousands, of copies of popular titles were published and circulated among a diverse readership, and books played a key role in disseminating ideas, information, literature, learning, high and low culture, entertainment, arts, crafts, and design across all social classes.

Subjects

The earliest subjects of Japanese illustrated books were classics of court literature such as Genji monogatari (The Tale of Genji), Ise monogatari (Tales of Ise) (fig. 9),and anthologies of court poetry. Printed editions made the texts of these works more widely accessible and fostered a broad familiarity with the scenes that had traditionally illustrated specific episodes or chapters. These scenes were also the frequent subjects of paintings. The interactions between illustrative cycles in painting and printed books during the seventeenth century are a provocative case study in the formation of a standard canon of illustrations of classical Japanese literature.

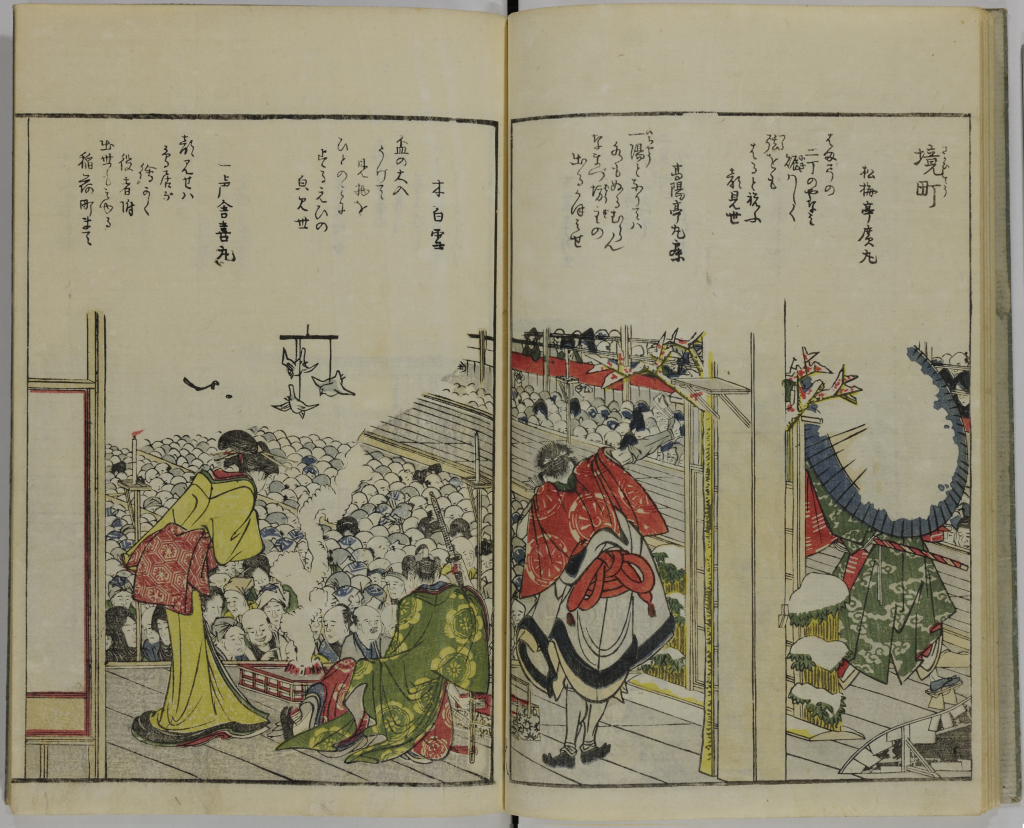

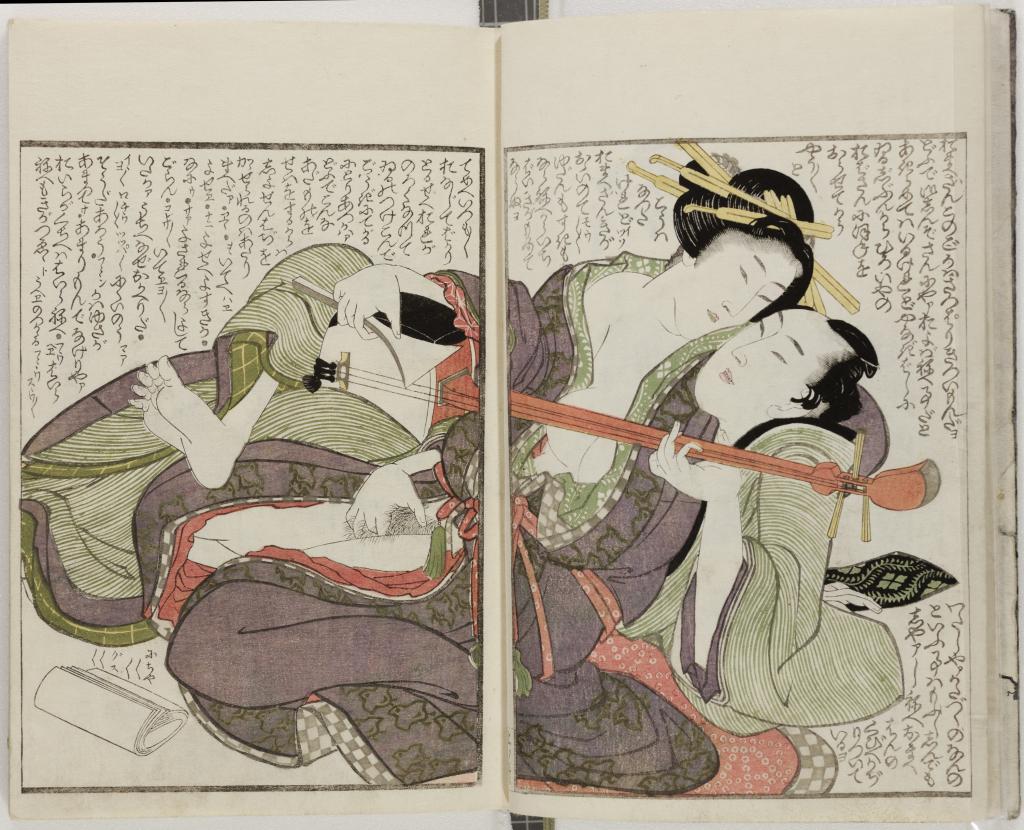

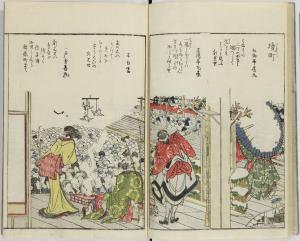

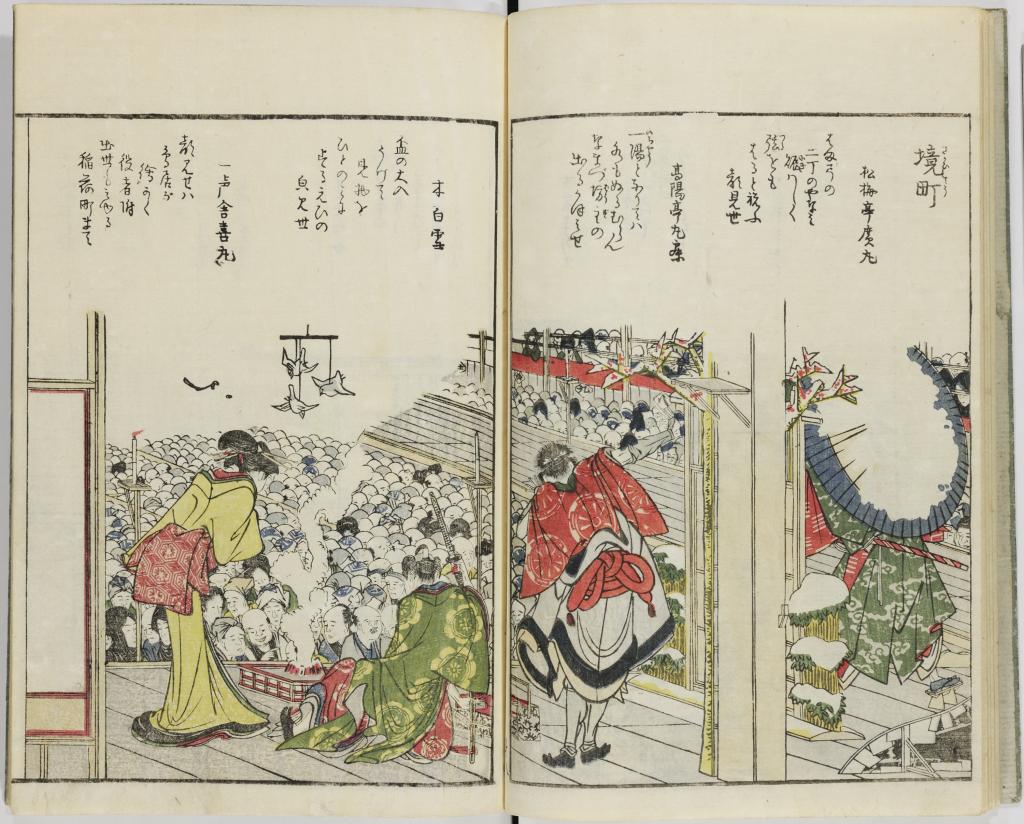

By the late seventeenth century, Kyoto publishers were also publishing illustrated books on contemporary subjects. With the rise of a successful, entrepreneurial, and wealthy merchant class came the flourishing of a vibrant urban popular culture. Among the new theatrical forms was kabuki, which was performed in theaters in Kyoto, its city of origin, and later in Edo and Osaka. Illustrated books portrayed kabuki performers. Books also presented scenes of the licensed pleasure quarters where women resided to entertain men with music, dance, poetry, and erotic companionship (fig. 10). Illustrations of the “floating world” (ukiyo) of entertainment and pleasure were especially popular subjects after the introduction of full color printing in 1765. Two of the most famous multivolume books in this genre are Ehon seirō bijin awase (1770)by Suzuki Harunobu (1724–1770) and Ehon butai ōgi (1770), a collaborative work by Katsukawa Shunshō (1726–1792) and Ippitsusai Bunchō (1764–1801) (fig. 11). Both provide elegant, full-color portraits—Harunobu’s idealized images of courtesans of the Yoshiwara pleasure district in Edo, and Shunshō and Bunchō’s more individualized portraits of kabuki actors in male and female roles, both of which were played by male actors. Books also provided images of contemporary poets, sumo wrestlers, and other celebrities offstage and behind-the-scenes, giving fans a sense of intimate inclusion in the luminaries’ worlds (fig. 12).

Many artists of ukiyo-e (pictures of the “floating world”) became involved in book illustration, and their successors continued to have an important role as illustrated book production spread to Osaka, Edo, and Nagoya. As these volumes proved profitable, publishers in the early eighteenth century began to print single sheets on ukiyo-e subjects, designed by professional artists and either hand-colored or printed in color as the technology evolved. Thus prints proliferated in parallel to books, for both the commercial market and noncommercial commission. For some publishers, who produced both books and single-sheet prints, the prints became an important and lucrative spinoff of the book-publishing boom, sharing technology, some subject matter, and artists.

Erotic subjects, although officially censored by the Tokugawa shogunate, were illustrated in printed books. Such books were often unsigned and the publisher unidentified, despite regulations that required this information to be printed in each volume (fig. 13). They were sold and circulated surreptitiously, although it is clear that buyers knew where to find them. Erotic book illustrations have recently begun to be studied and exhibited with greater interest by researchers and audiences, in part because of diminishing legal and social constraints in Japan and elsewhere.

By the second half of the eighteenth century, Edo, the largest city in Japan, with an estimated population of one million in 1721, was also the largest market for books on all subjects. Its distinctive contemporary culture, renowned for its contrast to the more traditional culture of Kyoto, was depicted in books that were popular among both residents and visitors to the city. Edo’s book publishers proliferated and established a dominant position in production of prose fiction and historical tales as well as staples for visitors such as maps and guides to the Yoshiwara and vibrant images of the city itself (fig. 14). Because of their importance to the quality of books, especially illustrations, block carvers were organized as a guild, the Hangiya nakama. It had 62 members in 1790, and grew to 223 members in 1852.7 There was also a booksellers’ guild, the Shomotsuya nakama. The growth of these guilds reflects the increase in publishing in Edo during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century.

Artists and Patrons

Illustrated books and, to a lesser extent, prints attracted painters trained in traditional ateliers such as the Kano and Tosa schools as well as artists who pursued innovative and international influences in Edo Japan. Book illustration gave artists an effective means for enhancing their livelihoods and reputations. Publishers paid them to create brush-and-ink sketches on thin paper, which was pasted face down on blocks as guides for the block cutter. In books from the early seventeenth century, the artists are not identified, but by the second half of the century their names are given in prefaces and colophons, most likely as a means for enhancing sales. As the skills of block cutters were critical to the fidelity with which an artist’s ideas could be realized, block cutters, too, are often named in fine illustrated books by famous artists. An example is Fugaku hyakkei (1834, 1835, and ca. 1849) by Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849) (fig. 15). Colophons contain valuable historical information on artists’ personal associations with scholars, writers, actors, designers, and on the affinity groups to which prominent cultural figures belonged.

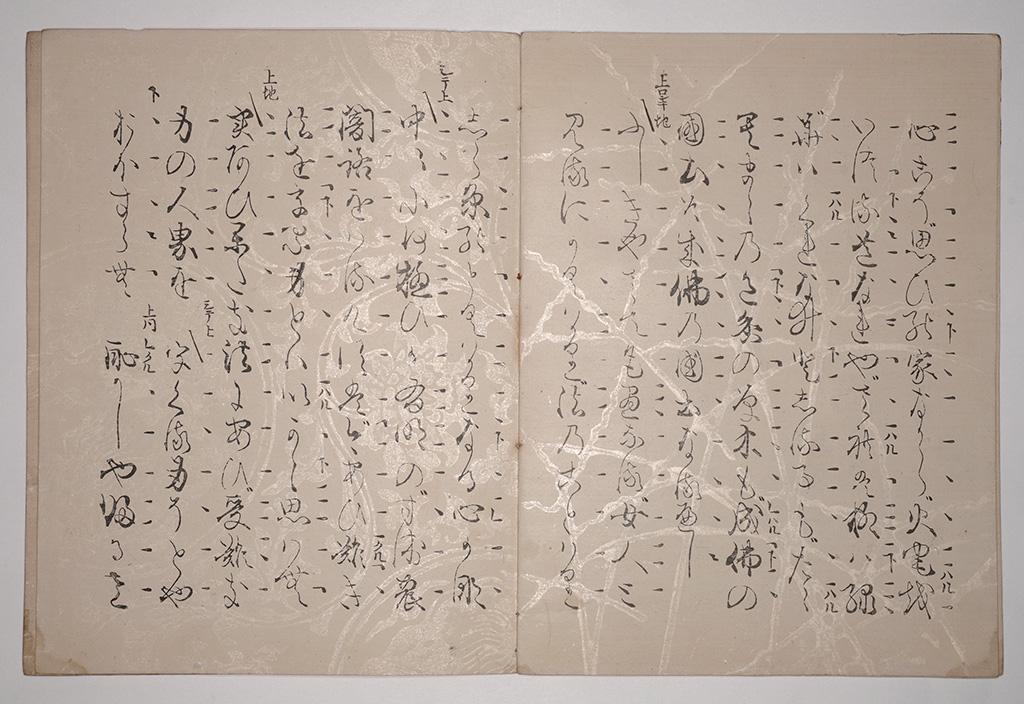

Some publishers produced fine printed books in small editions for affinity groups such as poetry circles and private patrons. The cost of materials and labor was higher for these books. Among them were volumes ofkyōka, comic verse, written by professional and amateur poets who often belonged to poetry clubs. Because the print runs for these volumes for limited circulation was small, they are often known today by single surviving volumes. An example is Kikkōjō 1822), a small memorial volume for the Osaka kabuki actor Arashi Kitsusaburō I (fig. 16). The only known example is in the Gerhard Pulverer Collection of the Freer Gallery of Art.

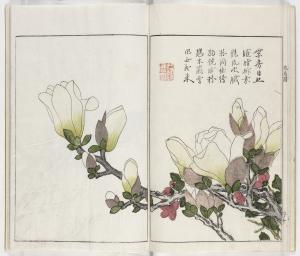

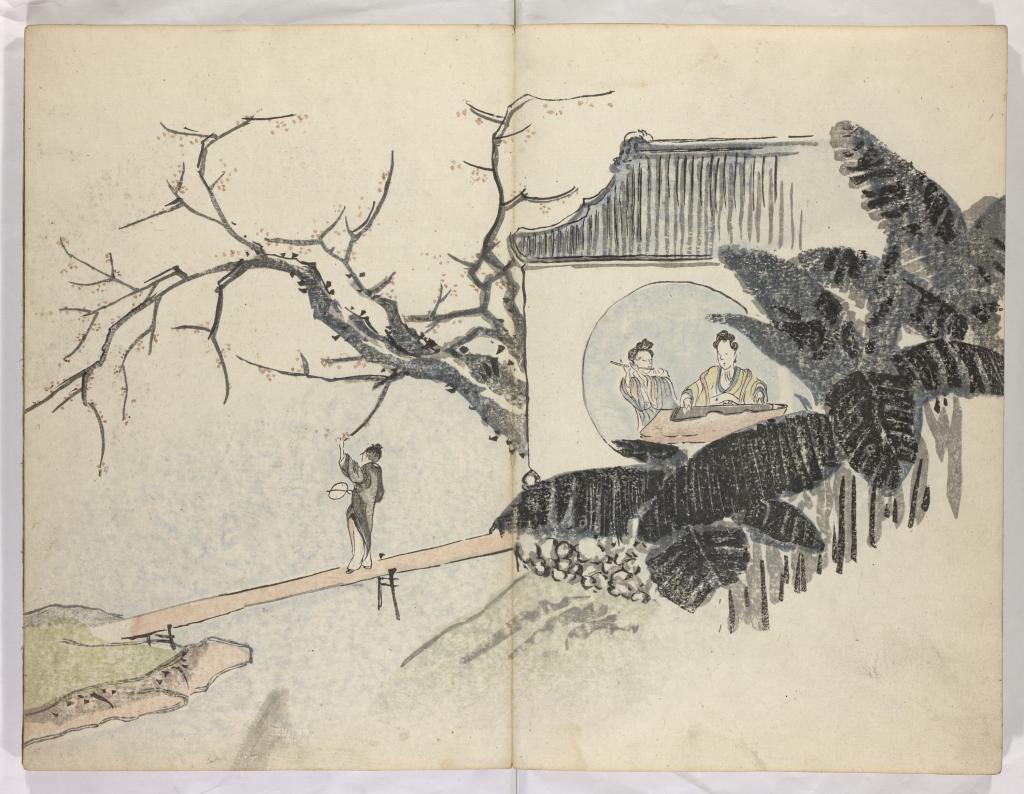

Although direct foreign trade and contact was legally restricted by the Tokugawa Bakufu to Chinese and Dutch traders at the port of Nagasaki, the Bakufu’s ideological support of Confucian studies ensured that the continuing cultural prestige of Chinese literature, philosophy, and art would be a strong current throughout the Edo period. Many Edo period Japanese scholars sought to emulate the ideal pursuits of Chinese scholars, practicing calligraphy, poetry, painting, musical performance, and reading in the Chinese language. Some of the most beautiful Japanese books are printed on fine Chinese paper in the elegant, elongated format that distinguishes Chinese books. Faithful full-color Japanese copies of painting manuals such as the Mustard-Seed Garden Manual, first published in China in 1679, provided instruction for artists seeking to paint Chinese subjects in a Chinese style (fig. 17). Only with the Meiji Restoration in 1868 following the resignation of the last shogun did Chinese studies decline under a new national advocacy for Japanese language, history, and culture.

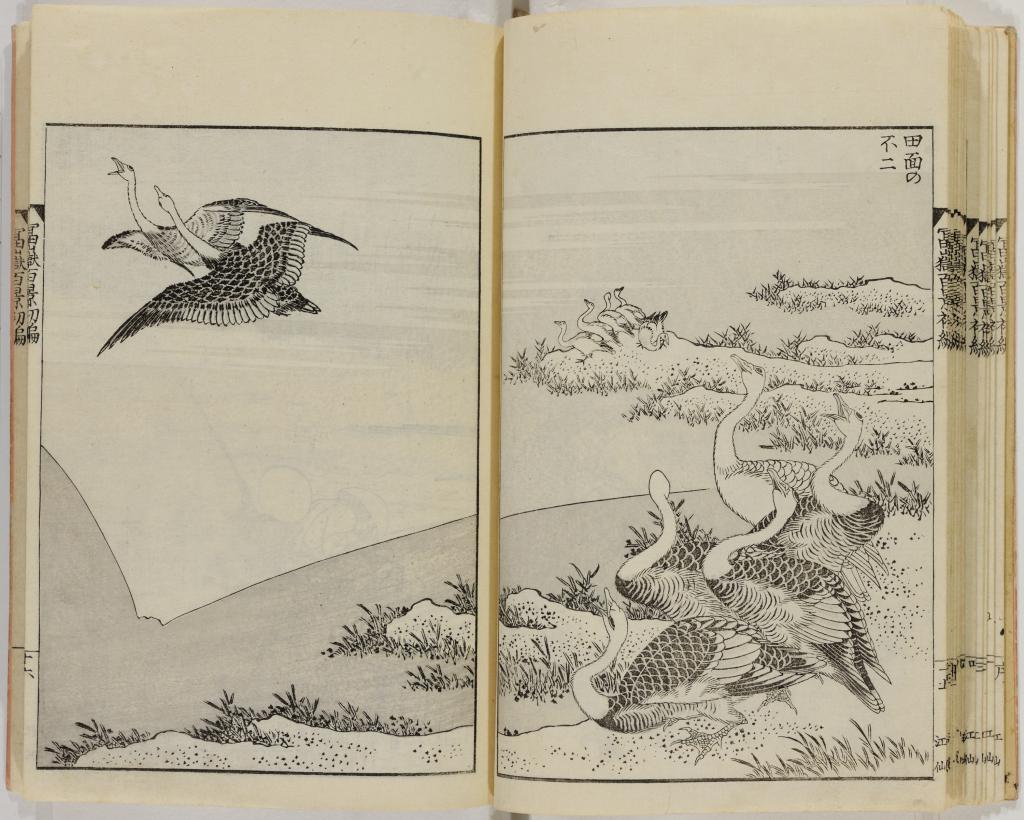

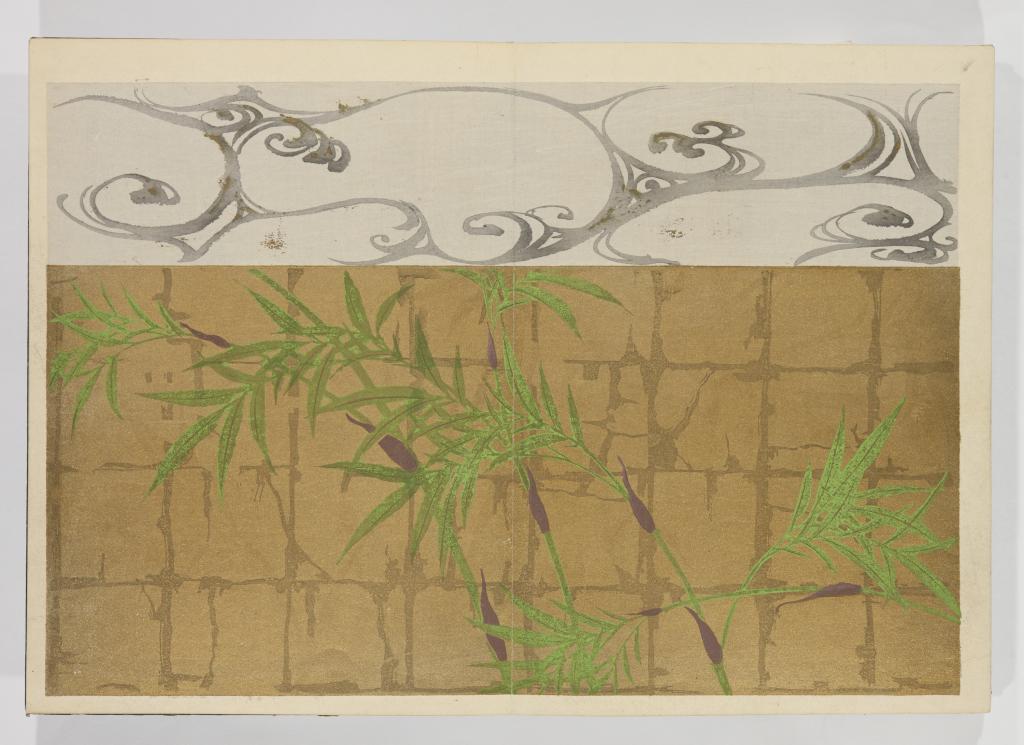

Japanese artists of the Nanga school, whose painting and calligraphy followed Chinese models, often created illustrations for gafu, books of paintings reproduced by expert woodblock printing that were bound as albums to enhance the illusion that they were painted with a brush and ink or watercolor. In such books, the skills of the block cutters and the printers re-created the nuances of brush and ink (fig. 18).

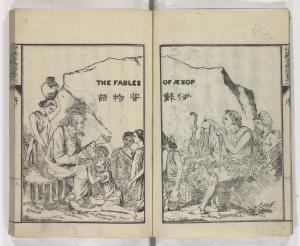

Despite the shogunate’s restrictions on foreign trade and prohibition of direct contact between foreign visitors or residents and the Japanese populace, books and knowledge from China and Europe were transmitted to Japan by books imported by Dutch and Chinese merchants at the port of Nagasaki throughout the Edo period. Copperplate printing, introduced by the Jesuit Mission Press, had declined as the practice of Christian worship was forbidden under early Tokugawa edicts, but Shiba Kōkan (1738–1818) and other artists learned the technique of etching. In the first part of the nineteenth century, copperplate printing and stylistic emulations of etching were novel, and etched images and alphabetic script were incorporated into some Japanese books (fig. 19). European books also introduced technical, scientific, and medical knowledge into Japan, preparing the way for increased contact with Europe and the United States in the nineteenth century.

Foreign Influence

During the decade preceding the end of the Tokugawa shogunate and the restoration of imperial rule that followed, Japanese leaders and intellectuals traveled to foreign countries. They brought books published in the West back with them, initiating changes in the physical formats, design, and eventually printing techniques used for Japanese books. Western-style books, with their hard covers and bindings, came to be considered as modern. During the Meiji era (1868–1912), such books, with typeset texts printed on presses, came into their own as commercially viable products of the publishing industry. Adaptation of modern printing and binding technology continued to advance, but the taste for fine woodblock-printed illustrations persisted well into the twentieth century (fig. 20). Imported newspapers also spurred the growth of a mass market for current news that has continued to the present day, and some of the largest and most influential multimedia corporations are the descendants of early news publishers.

Woodblock printing continued to be favored for specialized illustrations such as design books containing patterns that could be incorporated into textiles, lacquerware, or other craft designs. Larger sheet sizes bound with cord were created as albums showcasing beautiful works of art that also inspired artists in other media such as textiles and the decoration of lacquer, porcelain, and metalwork (fig. 21). The aesthetic qualities of woodblock printing, which differ from those of modern printing techniques such as lithography, have contributed to its longevity in the production of fine books. Some artists known for their self-published prints also created limited-edition woodblock-printed books in which they sought to create a uniquely beautiful object like the small edition printings of kyōka poetry during the Edo period.

Mass publishing has, however, shifted toward the newer technologies capable of producing large print runs and digital media for the voracious reading public that still exists in contemporary Japan. Publishers continue to identify specific readerships and to design their books accordingly. Just as in the publishing boom that began in the early seventeenth century, books range from recondite to pure entertainment, where manga (comic books) combining vivid illustrations with text recall the cheap mass publications of the Edo period.

Unfortunately, relatively few of these Edo period publications survive, especially good impressions in a good state of preservation and completeness, and estimating the numbers that were originally printed is difficult. Even the limited-edition specialized books were not systematically recorded or placed in repositories. Despite a history of collecting in Japan and in Europe, starting in the eighteenth century, clean, intact examples of specific titles are rare, even when thousands or tens of thousands of copies had once been in print. Japanese illustrated books are vulnerable to fire, separation, damage, loss, and a vogue in Japan during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries for the modernity of Western-style books and bindings that for a time devalued woodblock-printed books. All these circumstances contributed to losses that may still be ongoing.

Yet Japanese illustrated books contain a wealth of information about commerce, society, ideas, and art. While some can be appreciated for their sheer beauty, they offer much more to the scholars who are researching the many questions that remain about book production, circulation, and readership during the centuries before the emergence of electronic media.

Footnotes

Peter Kornicki, The Book in Japan: A Cultural History from the Beginnings to the Nineteenth Century (Leiden, Boston, and Cologne: Brill, 1998; paperback ed., Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2001), 129.

Kyoko Kinoshita, “The Advent of Movable-Type Printing: The Early Keichō Period and Kyoto Cultural Circles,” in Felice Fischer, The Arts of Hon’ami Kōetsu: Japanese Renaissance Master (Philadelphia, Pa.: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2000), 56–60.

Kornicki, Book in Japan, 134–35.

The New Year on the traditional Japanese lunar calendar fell in early spring. The notation haru (spring) in the colophon date of printed books indicates a New Year publication.

Kornicki, Book in Japan, 350–62, discusses the history, mechanisms, and scope of censorship in the pre-Edo through Meiji periods.

Kornicki, Book in Japan, 184.

Kornicki, Book in Japan, 202.

Bashō 芭蕉

Artist: Hon’ami Kōetsu (1558–1637)

Edo period, undated, early 17th century

1 volume; movable wood type and woodblock printed; ink and mica on paper; paper covers

24.2 x 18.1 x 0.4 cm

Freer Gallery of Art, FSC‑GR‑780.98

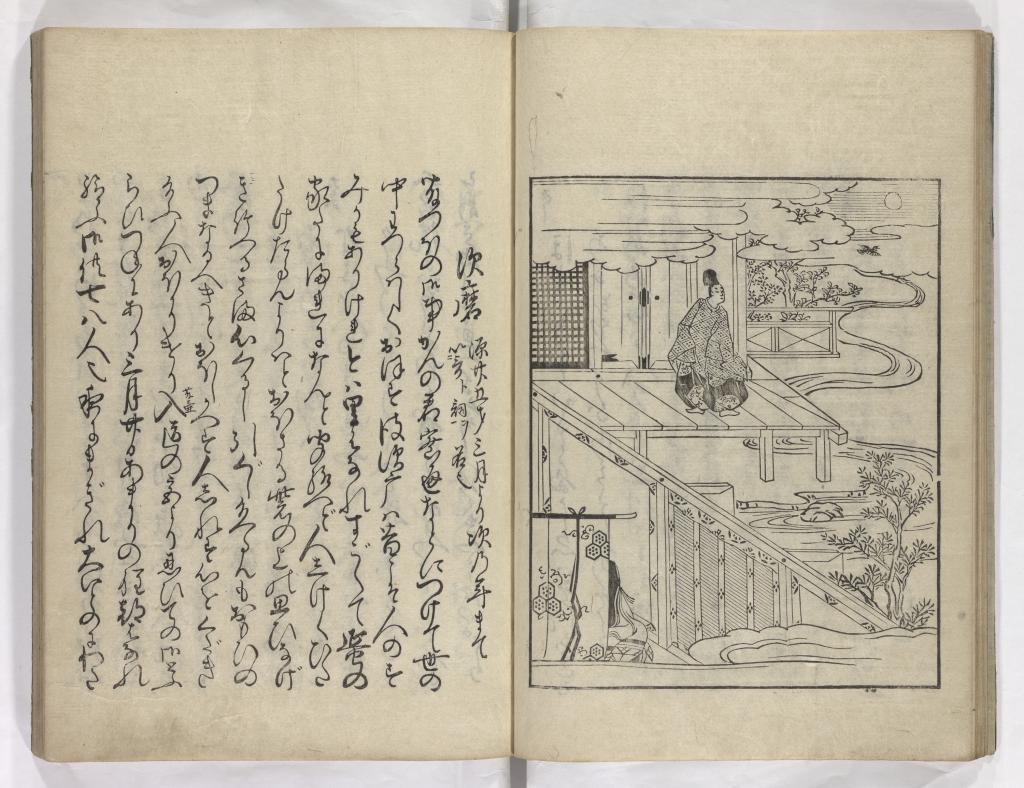

Jūjō Genji 十帖源氏

Artist: Nonoguchi Ryūho (1595–1669)

Edo period, 1661

Volume 3 of 10; fukurotoji binding; woodblock printed; ink on paper; paper covers

8.1 x 19.8 x 0.9 cm

Freer Gallery of Art, FSC‑GR‑780.469.3

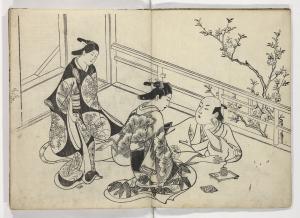

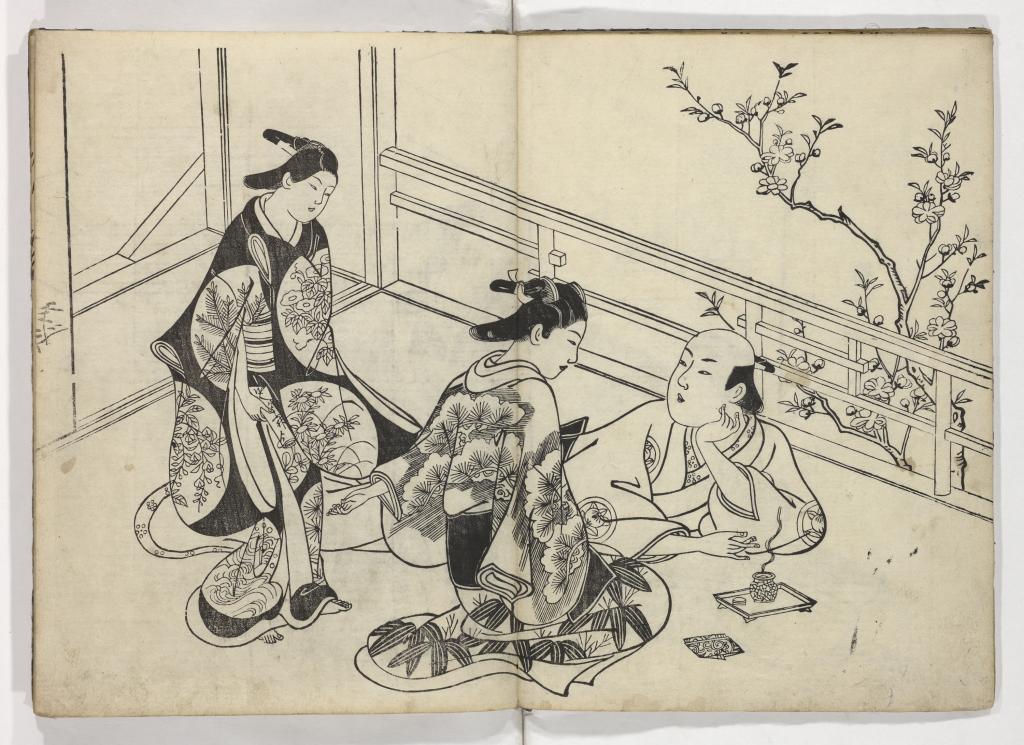

Genroku jinbutsu 元禄人物

Artist: Okumura Masanobu (1686–1764)

Edo period, undated, late 17th century

1 volume; gajōsō binding; woodblock printed; ink on paper; paper covers

26.4 x 18.7 x 0.7 cm

Freer Gallery of Art, FSC‑GR‑780.493

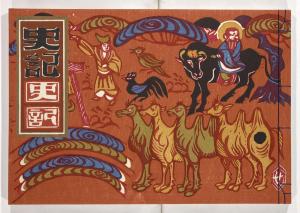

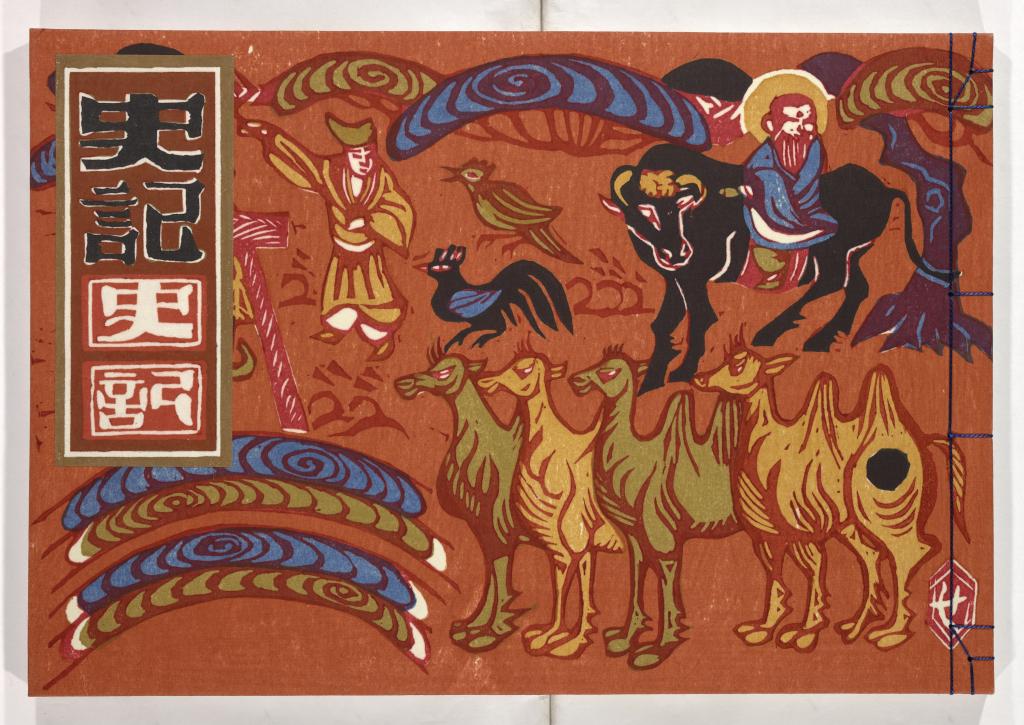

Kosetsu shiki 瞽説史記

Artist: Sekino Jun’ichirō (1914–1989)

1975

1 volume; fukurotoji binding; woodblock printed; ink on paper; color on covers and title page; paper covers

21.9 x 31.8 x 1.1 cm

Freer Gallery of Art, FSC‑GR‑780.531.1–2

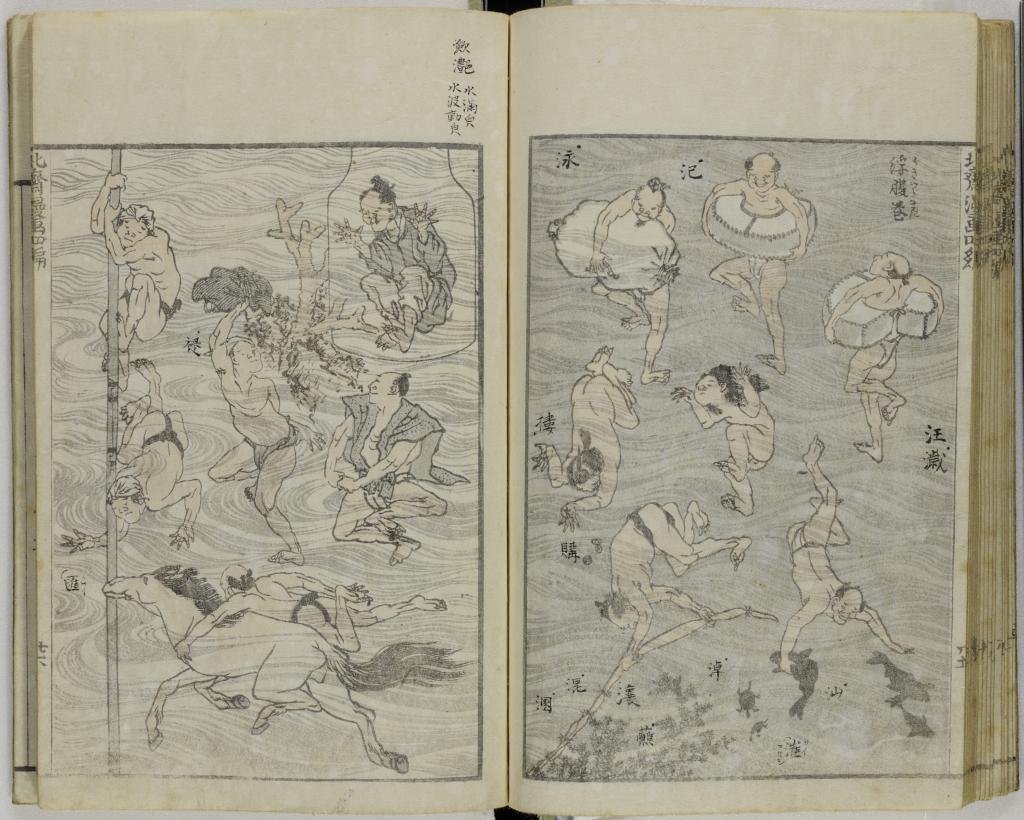

(Denshin kaishu) Hokusai manga (伝神開手)北斎漫画

Artist: Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849)

Edo period, 1816

Volume 4 of 15; woodblock printed; ink and color on paper; paper covers

22.9 x 15.9 x 1 cm

Freer Gallery of Art, FSC‑GR‑780.233.4

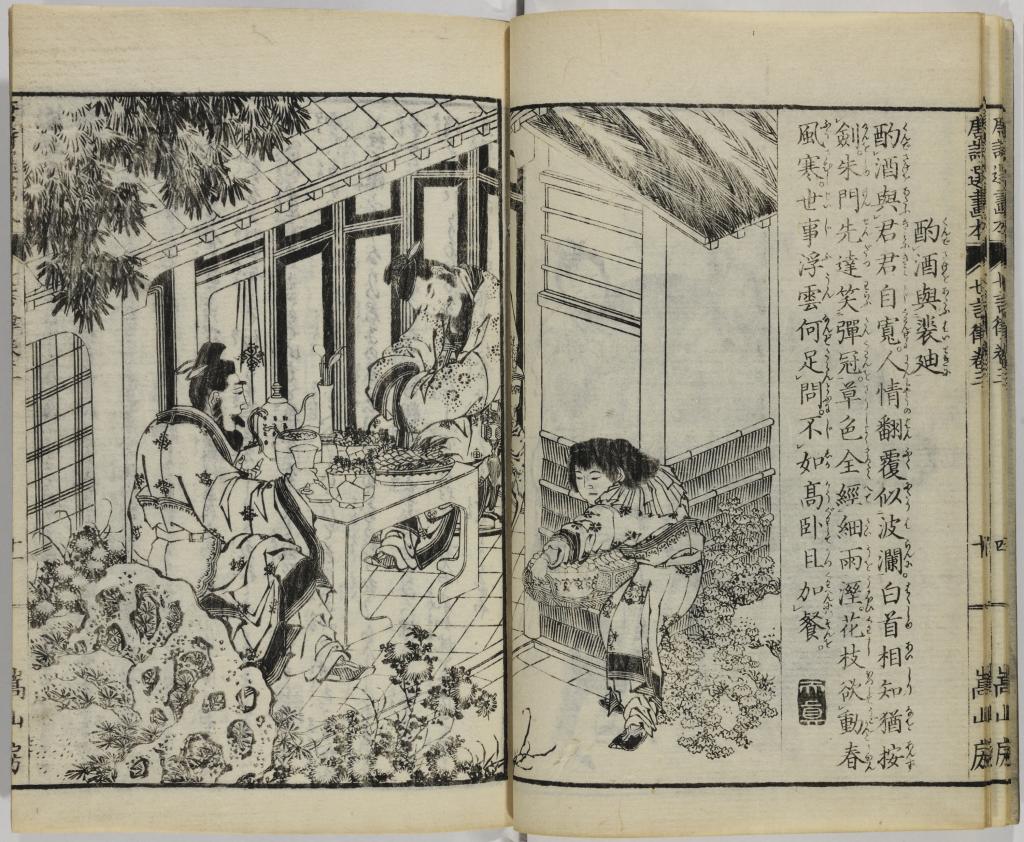

Tōshisen ehon shichigonritsu 唐詩選絵本七言律

Artist: Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849)

Author: Takai Ranzan (1762–1839)

Edo period, 1836 (Tenpō 7), 9th month

Volume 3 of 5; fukurotoji binding; woodblock printed; ink on paper; paper covers

22.8 x 15.7 x 0.4 cm

Freer Gallery of Art, FSC‑GR‑780.226.3

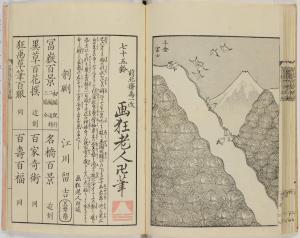

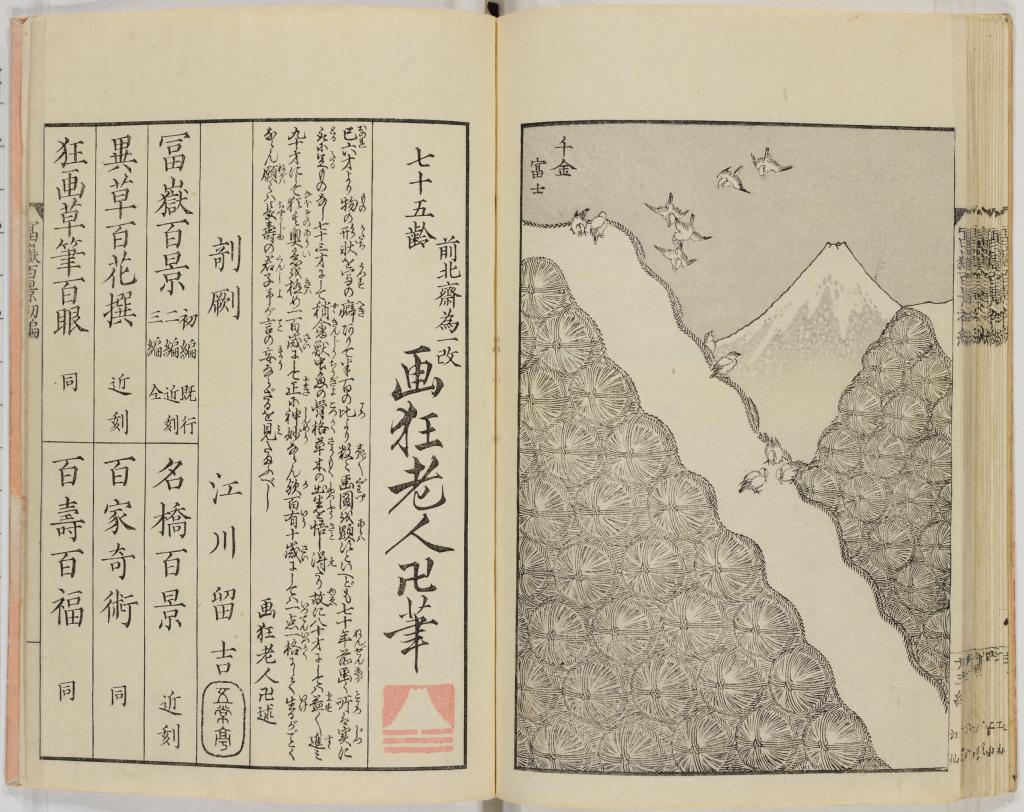

Fugaku hyakkei 富嶽百景

Artist: Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849)

Edo period, 1834 (Tenpō 5)

Volume 1 of 3; fukurotoji binding; woodblock printed; ink on paper; paper covers

22.9 x 15.8 x 1 cm

Freer Gallery of Art Study Collection, FSC‑GR‑780.246.1

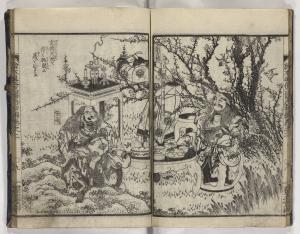

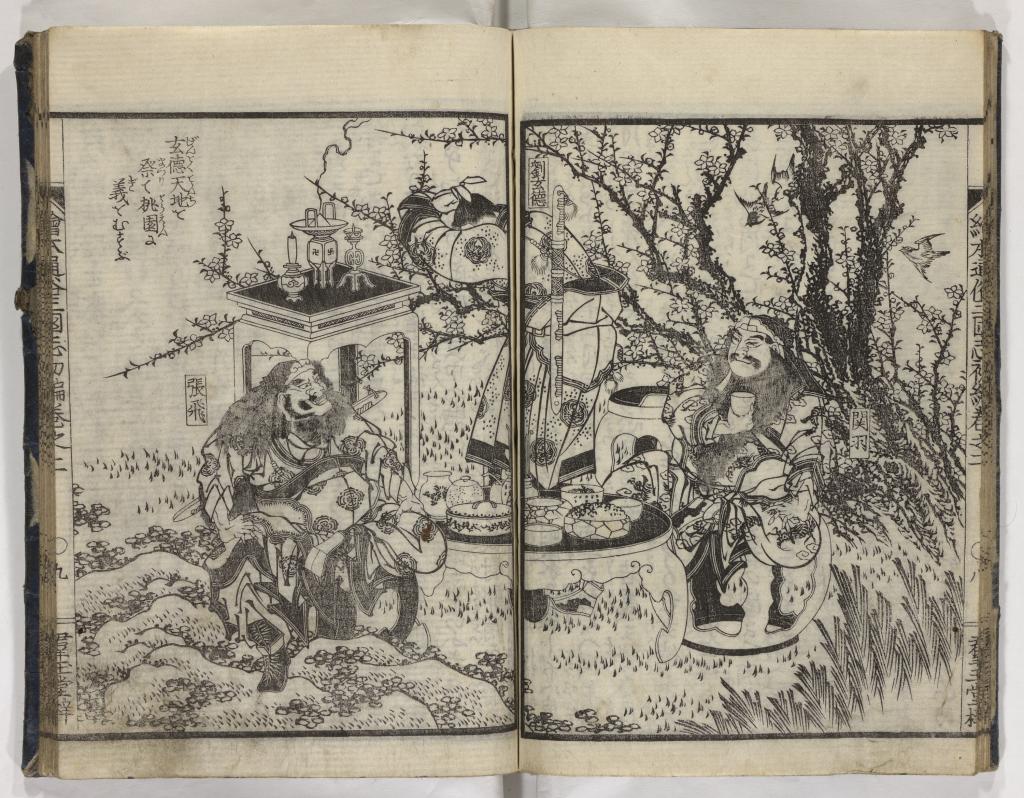

Ehon tsūzoku sangoku shi 絵本通俗三国志

Artist: Katsushika Taito II (active 1810–53)

Edo period, 1836–41 (Tenpō 7–12)

Volume 2 of 75 volumes; fukurotoji binding; woodblock printed; ink on paper; paper covers

22.4 x 15.7 x 1.1 cm

Freer Gallery of Art FSC‑GR‑780.271.2

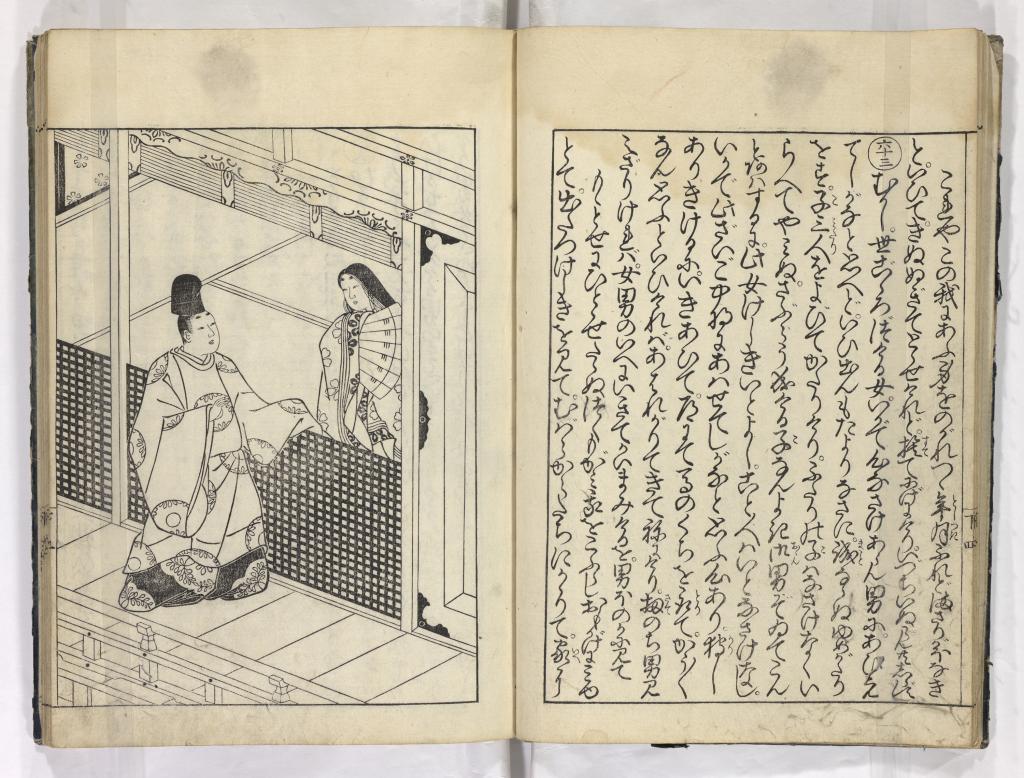

(Eiri) Ise monogatari(絵入)伊勢物語

Artist: Tsukioka Settei (1710–1786)

Edo period, 1756 (Hōreki 6)

Volume 2 of 2; fukurotoji binding; woodblock printed; ink on paper with hand-coloring on title pages; paper covers

27.1 x 19.5 x 1.1 cm

Freer Gallery of Art, FSC‑GR‑780.634.22

Seirō bijin awase sugata kagami 青楼美人合姿鏡

Artist: Kitao Shigemasa (1739–1820)

Artist: Katsukawa Shunshō (1726–1792)

Edo period, 1776 (An’ei 5), 1st month

Volume 1 of 3; woodblock printed; ink and color on paper; paper covers

27.9 x 18.6 x 1 cm

Freer Gallery of Art, FSC‑GR‑780.167.1

Ehon butai ōgi 絵本舞台扇

Artist: Katsukawa Shunshō (1726–1792)

Artist: Ippitsusai Bunchō (1764–1801)

Edo period, 1770 (Meiwa 7), spring

3 volumes; fukurotoji binding; woodblock printed; ink and color on paper; paper covers

28.5 x 19 x 0.9 cm

Freer Gallery of Art, FSC‑GR‑780.164.3

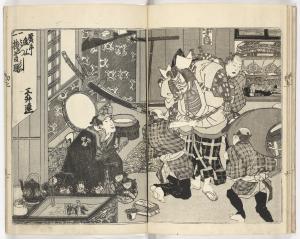

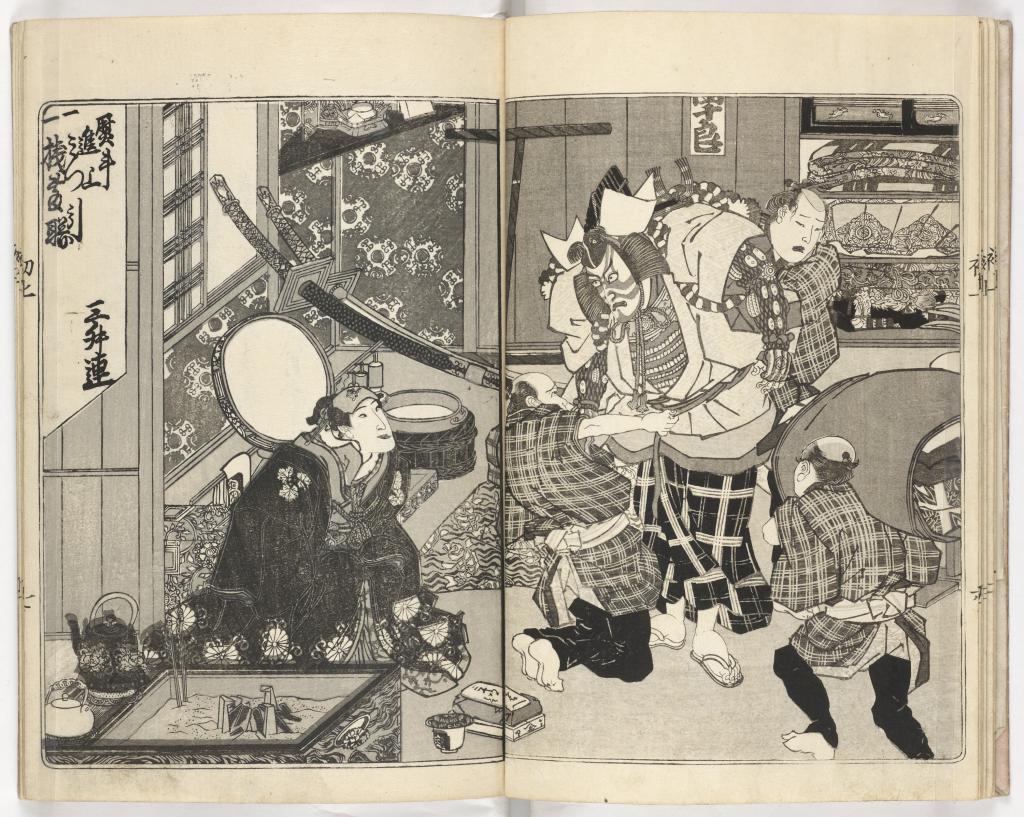

Yakusha kijin den 役者畸人伝

Artist: Utagawa Kunisada (1786–1864)

Edo period, 1833 (Tenpō 4), spring

Volume 1 of 4; fukurotoji binding; woodblock printed; ink on paper; paper covers

22.7 x 15.9 x 0.6 cm

Freer Gallery of Art, FSC‑GR‑780.713.1

Tamakazura 多満佳津良

Artist: Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849)

Edo period, undated, ca. 1820

Volume 1 of 3; fukurotoji binding; woodblock printed; ink, color, and metallic pigments on paper; paper covers

22.5 x 15.6 x 0.9 cm

Freer Gallery of Art Study Collection, FSC‑GR‑780.3.1

Tōto shōkei ichiran 東都勝景一覧

Artist: Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849)

Edo period, 1800 (Kansei 12), 1st month

2 volumes; fukurotoji binding; woodblock printed; ink and color on paper; paper covers

25.8 x 17.5 x 0.5 cm

Freer Gallery of Art, FSC‑GR‑780.217.2

Fugaku hyakkei 富嶽百景

Artist: Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849)

Edo period, 1834 (Tenpō 5)

Volume 1 of 3; fukurotoji bindings; woodblock printed; ink on paper; paper covers

22.9 x 15.8 x 1 cm

Freer Gallery of Art Study Collection, FSC‑GR‑780.246.1

Kikkōjō 橘香帖

Artist: Ashiyuki (active ca. 1814–33)

Edo period, 1822

1 volume; gajōsō binding; woodblock printed; ink, color, and metal leaf on paper

25.8 x 19.5 x 0.3 cm

Freer Gallery of Art Study Collection, FSC‑GR‑780.43

Kaishien gaden 芥子園画伝 (Mustard-Seed Garden Manual)

Edo period, 1748 (Kan’en 1), winter

Volume 4 of 6; fukurotoji binding; woodblock printed; ink and color on paper; paper covers

28.5 x 18.3 x 0.7 cm

Freer Gallery of Art, FSC-GR-812.4

Taigadō gafu 大雅堂画譜

Artist: Yamaoka Geppō (1760–1839), after Ike Taiga (1723–1776)

Edo period, 1803 (Kyōwa 3), winter

1 volume; gajōsō binding; woodblock printed; ink and color on paper; paper covers

29.5 x 19.5 x 1.6 cm

Freer Gallery of Art, FSC‑GR‑780.103

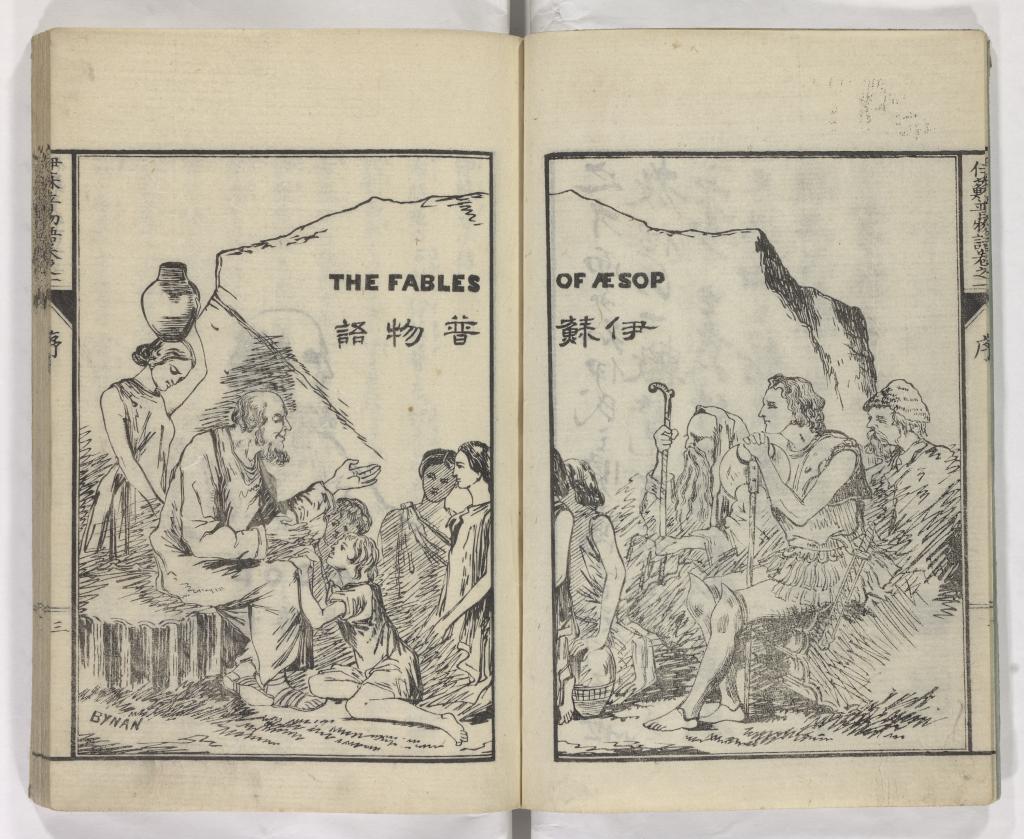

Tsūzoku isoppu monogatari 通俗伊蘇普物語 (Aesop’s Fables)

Artist: Kawanabe Kyōsai (1831–1889)

Meiji era, 1872–1875

Volume 1 of 6; fukurotoji binding; woodblock printed; ink on paper; paper covers

22.4 x 15.1 x 0.8 cm

Freer Gallery of Art, FSC‑GR‑780.300.1

Tokaidō gojūsan tsugi 東海道五十三次

Artist: Mizushima Nihofu

Taisho era, 1920 (Taisho 9)

1 volume; board cover; bound book in original slipcase; color woodblock prints (illustrations) and typeset text; ink and color on paper; paper hardcovers

19.3 x 13.4 x 2.8 cm

Freer Gallery of Art, FSC‑GR‑780.419.1

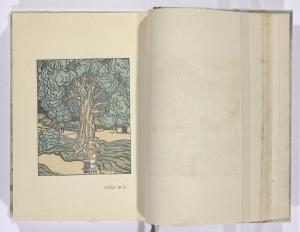

Kōrin moyō

Artist: Furuya Kōrin (1875–1910)

Calligrapher: Tomioka Tessai (1836–1924)

Meiji era, 1907 (Meiji 40)

Volume 1 of 2; gajōsō binding; woodblock printed; ink, color, and metallic pigments on paper; paper covers

25 x 18 x 1.1 cm

Freer Gallery of Art, FSC‑GR‑780.60.1